A Thank-You

With this post, the Half-Dipper happily marks its century.

As the subject of tea-writing has become discussed of late, I wondered if perhaps it would be a good time to write a little about the Half-Dipper itself.

First of all, to you, Patient Reader, many thanks for visiting. This humble collection of articles has a few goals that I set out on its creation (in no particular order):

i.

to provide an electronic repository of searchable information, combining factory details, leaf providence, information about the various genre of tea, and our tasting notes;

ii.

to stimulate discussion on the various teas, and to capitalise on the knowledge of the various tea drinkers that are generous enough to spend some of their time reading these pages;

iii.

to make and strengthen tea-friendships, sharing our thoughts and tea-samples with one another, and generally have a fine time with like-minded souls.

So, to you, Gentle Reader, I offer sincere thanks for your contributions in all of these areas. From the silent reader to the regular contributor, your visits to the page have helped transform it into something that I hope provides some benefit.

One of my quiet pleasures is perusing the statistics about the Half-Dipper readership, and it is something that I would like to share with you, as it underlines just how widespread the tea community really is - this is a marvellous thought given that even 15 years ago, such an endeavour would have been almost entirely impossible on any similar scale.

Click for an enlarged image. (Data shown derived from the fortnight ending today.)

Click for an enlarged image. (Data shown derived from the fortnight ending today.)Can you see your home-town? Approximately 50% of the 100-odd daily visitors come from the Americas, 30% come from Europe, and 20% come from Asia. In fact, it's interesting to note that there are very few visitors from Mainland China itself (excepting a handful of daily readers in Kunming, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing) - this is quite the irony, given that most of what we discuss here is the produce of China! Perhaps it's the so-called "Great Firewall of China" at work.

On Blogs

As some of you will know from private correspondence, I am not a fan of the conventional, autobiographical blog: I have many friends that write such sites describing the

minutiae of their lives. The site exists with

themselves as the subject and author. There is nothing inherently wrong with this style (even Pepys did it!), but it isn't my cup of tea, nor a direction in which I wished to take the Half-Dipper - which exists only for the three goals mentioned above.

However, in writing about tea, I've noticed that a certain element of humanism is required. In some of the great tea blogs that I enjoy (many of which are listed in "My Diurnal Digest" to the left), I have found that I like to read not just about the leaf itself, but about the context in which it appears. Like many, I enjoy the natural settings of

Tea Logic, the Oriental explorations of

MarshalN, the busy suburban surrounds of

Phyll, the tea-fields and tea-ceremonies of

Teamasters, and the

cosmopolis of

Chadao, to name just a few of the richly rewarding sites in that list. To that end, I have found a little of my own tea-drinking context naturally creeping into the Half-Dipper, while still keeping the tea the subject. This seems like a healthy balance, and reflects what I enjoy in the works of others.

On Half-Dipper Content

As a brief examination of the Half-Dippers

Index of Tasting Notes will show, we drink all types of tea. This is not, nor never will be, a "

pu'er blog", simply because Lei and I find enjoyment in every corner of the tea map.

Previously, I asked the readership to indicate preference for what they would like to read about - many thanks to those that did so. The results are as follows (from 44 respondents):

...which, more or less, follows Lei's and my own particular preferences. Looking at the Index of Tasting Notes, it is a happy coincidence that the teas considered fall into approximately similar proportions:

pu'er the most frequently-encountered, then

wulong,

hongcha,

lucha, and other teas. Hopefully, this means that, by sheer coincidence, the teas we explore in the Half-Dipper align fairly well with expectations.

With all that said, I would like to emphasise the sincere gratitude which we have to you, Patient Reader, in helping Half-Dipper along its rambling course.

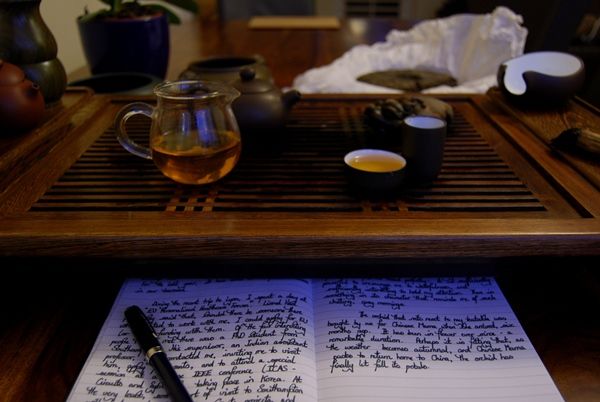

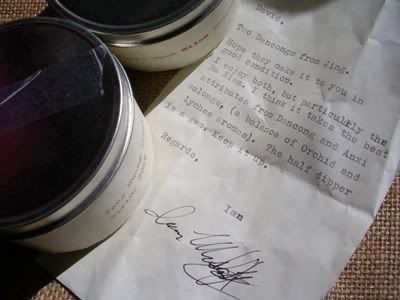

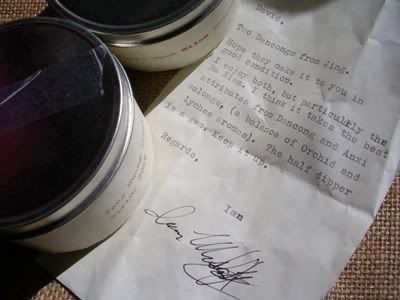

What better way to celebrate the Half-Dipper's century, than with a gift so generously sent by Ian (a.k.a.

ConquestOfBread). Given my love of all things anti-modern, you can well imagine my delight on finding that Ian's generous package was accompanied by a letter typed using a typewriter - quite the rarity these days, making the pleasure even sweeter upon receiving it:

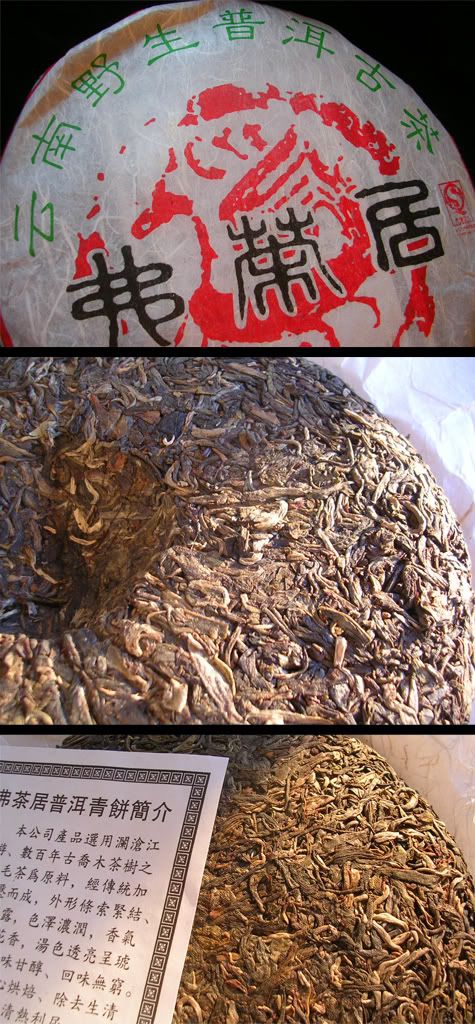

Without further ado, let's delve into the 2007

Baxian Dancong.

Selling at $24/100g from

Jing Teashop, this is a fairly low-priced tea, given its providence, listed as being true single-bush (of course the goal of

dancong, though many are blends from multiple bushes, often not in the same region). Ian notes a balance of orchid and

lychee. Notes on the

Baxian [8 immortals] genre can be found in a

previous post.

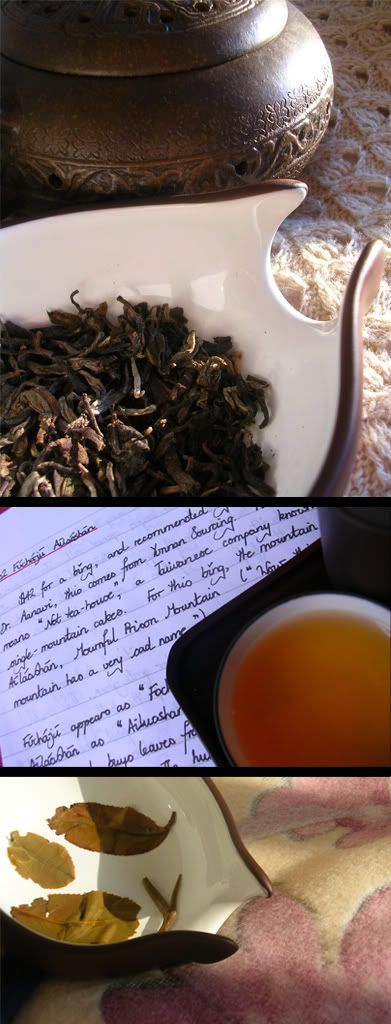

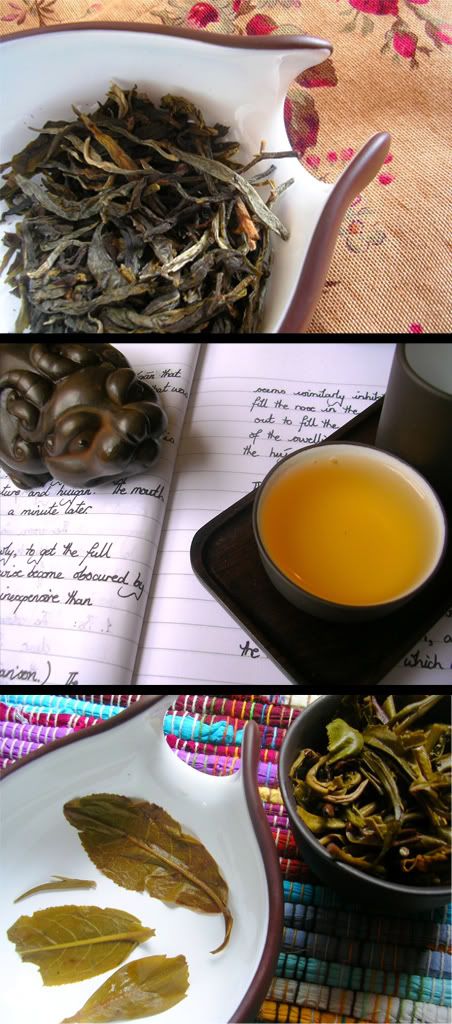

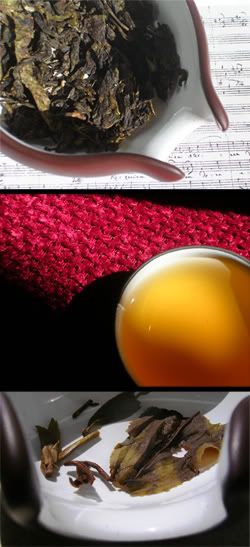

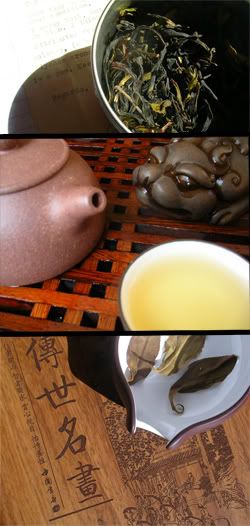

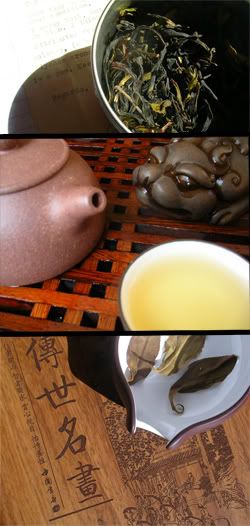

Brita-filtered water @ 90C in 10cl dancong pot; ~6-8g leaf; 1 rinse Dry leaf:

Dry leaf:Huge and beautiful, being 6-7cm of twisted leaf. Some are very dark, some remain very green, making an attractive contrast of the two types. This greener aspect is, to my understanding, typical of

Baxian.

12s, 10s, 15s, 22s, 40s, 60s:The radiant yellow-green soup reminds me that this is

gaoshan wulong, and it has impeccable clarity. The aroma is truly lovely, being both floral orchid and sweet/sour

lychee, just as Ian observed. The long, buttery-sweet

lengxiang is further evidence that this is based on a fine

gaoshan wulong leaf.

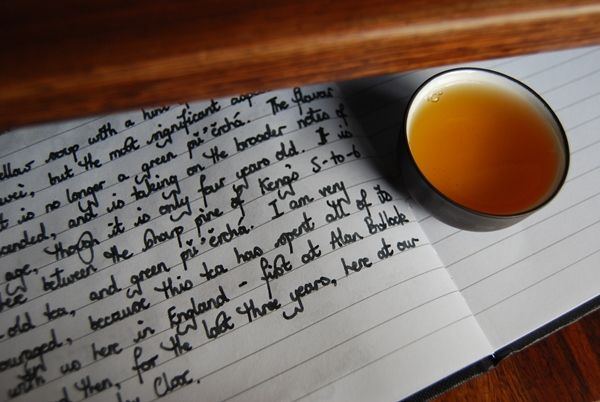

The tea is vivid, with a fine

chaqi rising up the throat and back. In comparison with the

second-grade Baxian from Royal Tea Garden, it is Heaven-and-Earth. There exists a wonderful sourness in the finish that results in a good

huigan. As in the

lengxiang, the buttery

yunxiang [aroma after the swallow] is pure

gaoshan excellence.

Even after six infusions, the tea, while simplified, remains very fine.

Wet leaf: Unusually healthy, these leaves are robust, quite thick, and verdant. The edges are brightly oxidised.

Overall:The basis leaf is of an excellent grade, as evinced when they are turned out of the pot for inspection and in the very good endurance shown during its evolution from infusion to infusion. On top of this, the oxidation and light roast have been expertly wed so as to work in symphony with the buttery

gaoshan characteristics, whereas they are so often imbalanced due to more coarse processing.

Couple these facts with the fairly low price (in comparison to those of other

dancong vendors) and this tea is an absolute winner. It is, without any reserve, the finest

dancong I have encountered. Profuse thanks to Ian for the generous gift, and the excellent choice.

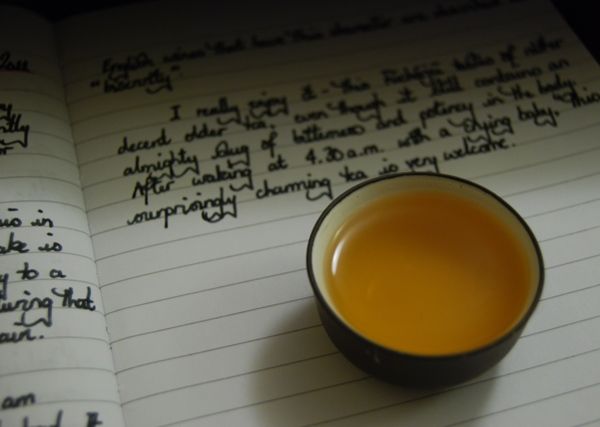

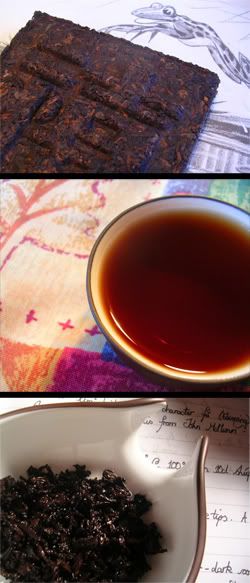

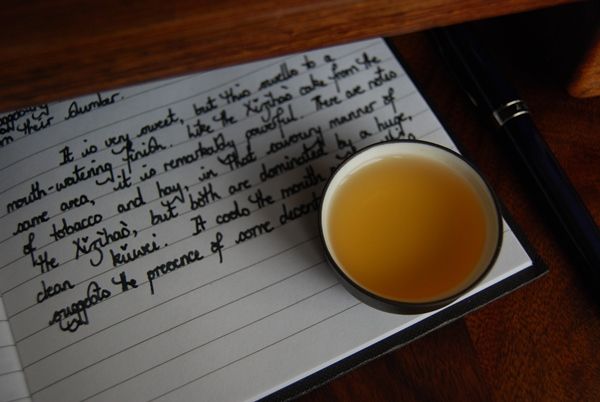

After just 4s, the soup is already pitch-black [pictured]. This is a rich, heavy little tea. The aroma is sweet wood, typical decent shicang. The texture of the liquid is thick and gloopy; it hugs the sides of the wenxiangbei.

After just 4s, the soup is already pitch-black [pictured]. This is a rich, heavy little tea. The aroma is sweet wood, typical decent shicang. The texture of the liquid is thick and gloopy; it hugs the sides of the wenxiangbei.