Induction heating is 95% voodoo, 5% science.

I hope that you will permit me to tackle a few misconceptions, including some particularly amusing ones in the Art of Tea magazine which VL may remember (though I've not bought this after the 3rd issue). I offer you the briefest of introductions to the black art of boiling your tea-water via induction.

I hope that you will permit me to tackle a few misconceptions, including some particularly amusing ones in the Art of Tea magazine which VL may remember (though I've not bought this after the 3rd issue). I offer you the briefest of introductions to the black art of boiling your tea-water via induction.

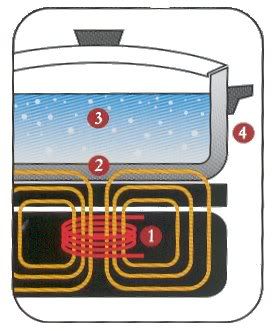

The main idea is that you have an electromagnetic coil tucked away in the base of your cooker (#1, in the figure). Most of the tea-inductors I've seen are made by Kamjove, and I've used one of those myself for about three years (though have recently changed to a hot-plate). It's primary benefit is that it's quick, because it's efficient.

Run some alternating current (a.c.) through the coil and, in accordance with the Biot-Savart law, you'll generate a magnetic field, as is well-loved by most physics classes in school. This magnetic field passes up from the coil, through the ceramic hot-plate sitting on top of your cooker, and into the metallic structure of your kettle (#2 in the figure). Remember that the current was a.c., so it's cycling positive and negative; and so, the magnetic field is cycling at the same frequency. Nice and easy so far.

Run some alternating current (a.c.) through the coil and, in accordance with the Biot-Savart law, you'll generate a magnetic field, as is well-loved by most physics classes in school. This magnetic field passes up from the coil, through the ceramic hot-plate sitting on top of your cooker, and into the metallic structure of your kettle (#2 in the figure). Remember that the current was a.c., so it's cycling positive and negative; and so, the magnetic field is cycling at the same frequency. Nice and easy so far.

The idea is, of course, to heat the water (#3 in the figure). This can happen in two ways, depending on what your kettle's made from.

i. Eddy currents

When you pull your oar through the water, you leave behind swirling vortices, persistent turbulence. When the magnetic field flickers on and off in the pot, you get an electric current induced in it (according to Faraday's law), circulating much like that persistent turblence caused by the oar. As every user of the light bulb will know, running current through metal causes heat to arise through resistance. This heat can be used to get your water boiling.

In induction cookers, however, this effect is negligible, and heating occurs from the second of the two methods:

ii. Hysteresis loss

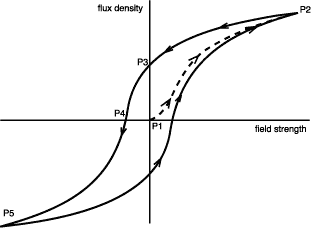

Check out the graph below. I know that most normal people are allergic to graphs, but hang in there.

This is what's happening as that magnetic field goes on and off in your kettle. That field is shown on the horizontal axis in the figure: "field strength". We start at P1. As the field gets stronger, that magnetic field is set up in the kettle. We can see the "flux density" (on the vertical axis) increasing as we increase the field strength, moving along that dashed line until we reach a maximum at P2.

Here's the useful bit: when the magnetic field flickers off again (moving back from P2 to P3), there remains some magnetism in the kettle. (This is what allows the creation of magnets, by the way.)

In fact, we have to reverse the field strength in order to get the flux density in the kettle down to zero again (P4). We reverse the field strength to its minimum (P5), and the flux density reaches its minimum. As we continue the cycle around once more (from P5 to P2), the flux density follows it as before - but "lagged". This cycle goes around and around as the a.c. current cycles between positive and negative.

This "lag" in the kettle's flux density is the hysteresis. The loop in the figure is a hysteresis loop, so called by engineering legend J.A. Ewing (although he was from the Other Place).

So how is this hysteresis heating my water?

Here's the useful bit: when the magnetic field flickers off again (moving back from P2 to P3), there remains some magnetism in the kettle. (This is what allows the creation of magnets, by the way.)

In fact, we have to reverse the field strength in order to get the flux density in the kettle down to zero again (P4). We reverse the field strength to its minimum (P5), and the flux density reaches its minimum. As we continue the cycle around once more (from P5 to P2), the flux density follows it as before - but "lagged". This cycle goes around and around as the a.c. current cycles between positive and negative.

This "lag" in the kettle's flux density is the hysteresis. The loop in the figure is a hysteresis loop, so called by engineering legend J.A. Ewing (although he was from the Other Place).

So how is this hysteresis heating my water?

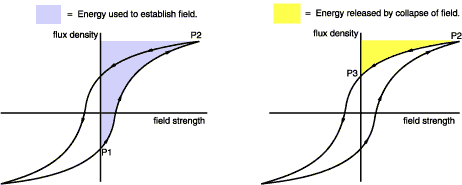

The purple (lilac?) area shown above is the work done (per unit volume of your kettle's material) in getting your kettle magnetised. When we relax the magnetic field, some energy is regained - as shown by the yellow area in the above. The difference between the purple and the yellow area is energy lost in the kettle - as heat.

The bigger the area between the curves (i.e., the greater the hysteresis), the more effective your kettle is at heating your water. So, induction kettles are typically made out of materials which satisfy this.

The heat generated is also proportional to the frequency with which the field cycles on and off. This can be up to 20 KHz, or 20,000 flickerings per second. Some people don't like the idea of sitting next to a 20 KHz magnetic field. A friend visited us for tea after spending many months in a meditative retreat, and he expressed discomfort around it. "Your mileage may vary" depending on your attitude to such things.

So, that's how your inductor works.

The bigger the area between the curves (i.e., the greater the hysteresis), the more effective your kettle is at heating your water. So, induction kettles are typically made out of materials which satisfy this.

The heat generated is also proportional to the frequency with which the field cycles on and off. This can be up to 20 KHz, or 20,000 flickerings per second. Some people don't like the idea of sitting next to a 20 KHz magnetic field. A friend visited us for tea after spending many months in a meditative retreat, and he expressed discomfort around it. "Your mileage may vary" depending on your attitude to such things.

So, that's how your inductor works.

"This article is so embarrassingly dull. What was that feeble human thinking?"

Inductors are very efficient: very little energy leaks out of the pot into the air - most of it is transmitted into the kettle, which heats the water. In contrast, conventional hobs just get hot: they heat the kettle, because it's nearby, but lots of energy also escapes into the air. So, an induction cooker is very fast at heating water, compared to conventional heating.

We can see that the ceramic hot-plate isn't there to heat the kettle, because that's being performed by the field - in fact, it's there's to insulate the fairly delicate induction circuitry from the hot kettle. To stop it overheating, it needs to be cooled from underneath, and so tea-versions usually have a noisy fan roaring away. I don't like this about induction cookers. It really ruins the tea atmosphere.

Induction also has lots of other fun applications: as the water heats, the characteristics of the field change, which can be sensed by the induction unit, and so the field can be changed to compensate. This allegedly leads to induction kettles with temperature control - but they're usually fairly horrible. I've not seen one that I could trust so far, and it's infinitely easier (and more reliable) just to learn it yourself - and more satisfying.

Induction also requires some resilient materials. The magnetic field is always set up in the same way, and the location of the most heated areas is concentrated spatially - it's not an "all over" heat, like a conventional hot-plate would provide, but appears in regular "hot spots". You're heating the base of your vessel in a fixed pattern, repeatedly, and the (really rather significant) temperature differential across the metallic lattice can lead to stress fractures. Don't put your expensive Japanese kettle on an induction hob!

So, that's induction. If you knew it all already, do please correct me where I'm wrong. If you didn't know (or care to know), then I hope it's been useful in some small way.

Either way, I hope I don't read any more stories about electricity passing through the water to heat it up!

Art of Tea, I'm looking at you...

We can see that the ceramic hot-plate isn't there to heat the kettle, because that's being performed by the field - in fact, it's there's to insulate the fairly delicate induction circuitry from the hot kettle. To stop it overheating, it needs to be cooled from underneath, and so tea-versions usually have a noisy fan roaring away. I don't like this about induction cookers. It really ruins the tea atmosphere.

Induction also has lots of other fun applications: as the water heats, the characteristics of the field change, which can be sensed by the induction unit, and so the field can be changed to compensate. This allegedly leads to induction kettles with temperature control - but they're usually fairly horrible. I've not seen one that I could trust so far, and it's infinitely easier (and more reliable) just to learn it yourself - and more satisfying.

Induction also requires some resilient materials. The magnetic field is always set up in the same way, and the location of the most heated areas is concentrated spatially - it's not an "all over" heat, like a conventional hot-plate would provide, but appears in regular "hot spots". You're heating the base of your vessel in a fixed pattern, repeatedly, and the (really rather significant) temperature differential across the metallic lattice can lead to stress fractures. Don't put your expensive Japanese kettle on an induction hob!

So, that's induction. If you knew it all already, do please correct me where I'm wrong. If you didn't know (or care to know), then I hope it's been useful in some small way.

Either way, I hope I don't read any more stories about electricity passing through the water to heat it up!

Art of Tea, I'm looking at you...

I love your cat ! a strong caracter, I see ... and I like the way you make associations between nature pictures and tea...

ReplyDeleteDear Gingko,

ReplyDeleteThank you for noticing! You know, I take a secret and deliberate pleasure in introducing something of a kigo into the relationship between images and text, no matter how clumsy my execution...

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Intriguing post although I seem to be breaking out in hives. I do love the way you bring the ruler Heidu into the picture and your backyard forays are fascinating and beautiful.

ReplyDeleteGood ol' Heidu. He can be a cruel overlord, but at least he looks cute.

ReplyDeleteHello Hobbes,

ReplyDeleteSo it looks like the puerh gods will be sticking with the voodoo part of induction heating =D! Good post. The humour and information are both greatly appreciated!

Have a good day,

Alex

Excellent post! I was taught that the induced current and resulting heat was the main reason the pot got hot. I failed to question this, and so I never saw any advantage over induction vs conduction. Now I know better.

ReplyDeletePS How loud is the hum from the 20KHz?

Dear Alex,

ReplyDeleteGlad you liked it.

Dear Newell,

The 20 KHz field is generated by a coil - it's effectively silent. What isn't silent is (i) the roaring fan under the ceramic plate, and (ii) the incessant, annoying beeps that Kamjove insists are made every time the user pushes a button - horrifically noisy!

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

The alchemy of Induction; just the ticket for those (clumsy) that tend to burn easily.

ReplyDeleteSemisonic - Chemistry Lyrics

“I remember when I found out about chemistry

It was a long, long way from here

I was old enough to want it but younger than I wanted to be

Suddenly my mission was clear

So for awhile I conducted experiments

And I was amazed by the things I learned

From a fine fine girl with nothing but good intentions and a

Bad tendency to get burned”

Perfecto! A few ideas sprang to my mind for at-home brewing. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteDear John,

ReplyDeleteYou can still get burned by an induction kettle!

Dear Anon,

Always a pleasure - thanks for the comment, whoever you are :)

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

I am so grateful for this post.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for taking the time! Yay science!

Dear Jason,

ReplyDeleteVery welcome - your first post here, too, I think!

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Great post! I also laughed at the idea of electrical current passing through my water (sigh), but I didn't know enough about induction kettles (just regular ol' conduction, but that's easy) to give a good explanation of how they work. Thank you!

ReplyDeleteBrent

Dear Brent,

ReplyDeleteAh yes, a classic article that was. :)

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Also grateful for the post... BUT, I think the snarky comments about electricity passing through the water are mostly about kettles with a coil type heater that's actually inside the kettle (like standard electric kettles). I think they're also trying to imply that a pot sitting directly on coils (vs. sitting on a metal plate heated by coils) might be somehow sending energy "through" the water, but I don't know that for sure.

ReplyDeleteI have to agree that some of these worries seem like BS to me. I can say that induction does seem to boil the water in a slightly different way than heating something over a fire or burner / hot plate. On the other hand, fast is supposed to be good, and induction can heat really, really fast at times.

There seem to be some pretty knowledgeable folks on either side of this debate. I'm using glass right now, so induction is kind of out of the question no matter what.

Dear Will,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comment - you know, I can't remember too much about those Art of Tea articles to be honest. I do remember being amused by them, though, and then re-amused when VL reminded me of them when we met!

I don't see it as much as a "debate", to be honest. Induction works one way, hot-plates work another, conventional resistive-coils-submerged-in-water work in another. You pays your money, you takes your choice. :)

My own choice is against induction, but that was a recent choice, and largely influenced by practical concerns no more elegant than the racket made by the Kamjoves.

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Being burned by:Induction vs. Open Flame, is a Darwinian sorting of the flock. :)

ReplyDeleteDear John,

ReplyDeleteIs burning by induction anything like proof by induction? They seem related!

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

No one expects the: “Induction Inquisition “ cheers john

ReplyDeleteOkay...I have not read the article so I could be way off base...but...

ReplyDeleteWater is seen as very important and therefore so is its source. Preferably from a natural stream? Not only for the mineral content but also because of the ionic charges that are created from its environment....movement of water molecules among themselves in a direction with rocks etc.

Perhaps what they are talking about without saying this specifically is that the magnetic fields generated from this type of heating effect the molecular structure of the water...changing the ionic charges therefore reducing or eliminating the naturally occurring and beneficial ionic charges within the molecules thereby giving a diminished experience.

Just a thought :)

Thanks for the thoughts, PK - actually, in the interests of fairness, I went back and dug out my old issue 2 of "Art of Tea" - it turns out I bought two, not three.

ReplyDeleteThe article specifically mentions energy-like changes of passing electricity through some channel through the water, just as Will said above, so it's unfair of me to say that they were describing induction heating. That's the residual of a joke on that subject between VL and me, I think.

I reread parts of the magazine while I was eating my breakfast this morning. Let's just say, I'm glad the "The Leaf" is being published, as it's a much better read.

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Once again you rule! First time I laughed in 3 days. Is Heidu Burmese?

ReplyDelete- Scott

I have absolutely no idea! I think he's part canine - I caught him rolling in the dust of a vegetable patch earlier in the week, just the way dogs do...

ReplyDeleteToodlepip,

Hobbes

He's gotta be mostly Burmese... we had a Burmese that lived to 19 years of age and every time he escaped to the outside he would roll in the dust. Those smug eyes!

ReplyDelete- Scott

I was thinking more "coolly calculating" than "smug", but you're probably right. :)

ReplyDeleteI'll ask his owners if he's Burmese!

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Too bad Heidu doesn't appreciate electromagnetic permeability.

ReplyDeleteI'm curious about knowing what would happen if I built a transformer where a metal pipe filled with saline water was used in place of the the normal laminated iron core. Assume the primary and secondary windings run at 60 cycles per second. Some transfer would take place. But, what kind of a transformer core would this arrangement make and would the water start to boil???

ReplyDeleteThere's only one way to find out!

ReplyDeleteWow! Thanks for this. I studied physics in univ and really, really enjoyed your hysterisis graph and explanation.

ReplyDeleteHey total aside, but jolly good reading...on the topic of ionic properties of water, there's a chapter on homeopathy in "13 Things that Don't make Sense" by Michael Brooks.

Soo... I like the energy-saving idea of an induction kettle, and the idea of adding iron to my diet with a tetsubin. I have to ask, have you since found an induction plate that works well with a tetsubin but doesn't have a noisy fan? I'm in the market for both a tetsubin and an induction plate...

Dear Liesl,

ReplyDeleteThanks for leaving a comment - your first on the Half-Dipper, methinks? :)

To answer your question, I have stopped using my induction hob (and did so when I wrote this article, in fact). I much prefer the resistive heat of a hob to the a.c. field of the induction system. I'm just a hippy, dressed up as an engineer.

All the best,

Hobbes