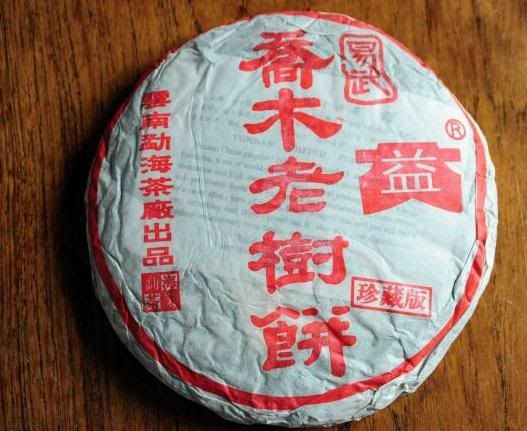

Phew! This tea has so many incidents of what a tort lawyer might call "passing off" that I don't know where to begin. Let's start at the top.

A wise man once said, "I won't buy anything from a factory with 'Menghai' in its name, unless it's Menghai Tea Factory." This is sound advice. There are approximately 6.022 x 10^23 tea factories with "Menghai" in their names, and 1.0 of them produce good tea.

So, let us consider "Menghai Pengcheng" (Menghai Peng Chen, at Puerh Shop), a factory so rare and obscure that it isn't even in Babelcarp (at the time of writing!).

Before we consider the name further, allow me an apostrophe. I have much for which to thank my school (probably what would be called a "High School" in American), but of particular note is the fact that they made us read quite a few of the Chinese classics (in translation - we were just babies). This came in particularly handy when strolling on the beach at a conference with a lovely lady who would eventually become suckered into being my wife.

A wise man once said, "I won't buy anything from a factory with 'Menghai' in its name, unless it's Menghai Tea Factory." This is sound advice. There are approximately 6.022 x 10^23 tea factories with "Menghai" in their names, and 1.0 of them produce good tea.

So, let us consider "Menghai Pengcheng" (Menghai Peng Chen, at Puerh Shop), a factory so rare and obscure that it isn't even in Babelcarp (at the time of writing!).

Before we consider the name further, allow me an apostrophe. I have much for which to thank my school (probably what would be called a "High School" in American), but of particular note is the fact that they made us read quite a few of the Chinese classics (in translation - we were just babies). This came in particularly handy when strolling on the beach at a conference with a lovely lady who would eventually become suckered into being my wife.

We studied a bunch of great texts that I honestly believe that most people would benefit from reading (Laozi, Liezi, Mozi, Kongzi/Confucius, some of the Yijing), but my favourite was Zhuangzi, the Daoist chap who wrote really witty material, following the Daodejing. I'm frivolous by nature, and Zhuangzi appeals to me. Near the start, he describes a huge, mythical bird-like creature called the "Peng", which travels bazillions of miles with its huge wings. There is a phrase in it, "Peng cheng wan li", meaning approximately "The peng journeys 10,000 miles". This has come to be a synonym for describing success in Chinese, perhaps a bit like the English "He's come a long way", or "He'll go far".

So, the two characters "Pengcheng" refer to this common saying. I instantly became impressed that the tea factory would name themselves after a phrase in the Zhuangzi, given that my prior assumption is that all tea factories are run by oily merchants with little interest in the classics. (Harsh, but fair.) However, my dear wife brought me down to earth, saying that the phrase "Peng cheng wan li" was in such common use that it would be like someone using a common Shakespearean phrase, probably without knowing its origins.

It's minutiae like this that divert me for hours.

So, the tea.

So, the two characters "Pengcheng" refer to this common saying. I instantly became impressed that the tea factory would name themselves after a phrase in the Zhuangzi, given that my prior assumption is that all tea factories are run by oily merchants with little interest in the classics. (Harsh, but fair.) However, my dear wife brought me down to earth, saying that the phrase "Peng cheng wan li" was in such common use that it would be like someone using a common Shakespearean phrase, probably without knowing its origins.

It's minutiae like this that divert me for hours.

So, the tea.

This has been labelled "yuanyexiang", translated characterwise as "primeval wild aroma" by the mighty Babelcarp. I think this time, I'm with the Puerh Shop translation, which has "prairie bouquet", noting that "yuanye" is a compound, which refers to open country, the champagne or campania. My Chinese language book wisely states, "Ask not how many characters a person knows in Chinese, but how many compounds." So, I would translate "yuanyexiang" as "Open-country aroma" or something along those lines. It's the scent of the great, unkempt outdoors.

This is the second instance of passing-off for this tea, because it cannot be coincidence that it refers to an appelation made rather famous by Shuangjiang Mengku, and others.

Finally, in the centre of the bing, we have the ubiquitous characters: pu'er wang [pu'er king].

Before we even look at the leaves (above), we have a whole mountain of prejudice, bias, and a priori assumptions to overcome. It is overwhelmingly likely that this tea is poor. I would be happy to be proven wrong... but Ouch's Menghai rule (see above) is seldom wrong. Let's find out.

This is the second instance of passing-off for this tea, because it cannot be coincidence that it refers to an appelation made rather famous by Shuangjiang Mengku, and others.

Finally, in the centre of the bing, we have the ubiquitous characters: pu'er wang [pu'er king].

Before we even look at the leaves (above), we have a whole mountain of prejudice, bias, and a priori assumptions to overcome. It is overwhelmingly likely that this tea is poor. I would be happy to be proven wrong... but Ouch's Menghai rule (see above) is seldom wrong. Let's find out.

"A true exciting pu'er experience!", writes the product web-page. "One thing we are talking about a lot is the aging potential if a tea is worth keeping, you can be sure this one got it, and it shows." (sic)

The leaves are small, with compression typical of a machine-pressing. They are a touch dark, and the few tips present in the blend have turned a beige colour, placing it around the 4-5 year mark, which may not come out too well in the photograph. The aroma is decent: full sweetness, with a body of grain. It has some spicy greenness about it that I usually associate with cheaper teas.

The first infusion is cloudy orange. The aroma is generically sweet, but in the mouth it is instantly and aggressively green. The product page notes that the leaves are from Bulang, and I can believe it, because this tea is heavy going. It isn't punchy, clean, and fresh, like the 2009 Nadacha "Bulang Qiaomu", instead being the brutal harshness of the plantation. It's raw, and it hurts the throat.

The leaves are small, with compression typical of a machine-pressing. They are a touch dark, and the few tips present in the blend have turned a beige colour, placing it around the 4-5 year mark, which may not come out too well in the photograph. The aroma is decent: full sweetness, with a body of grain. It has some spicy greenness about it that I usually associate with cheaper teas.

The first infusion is cloudy orange. The aroma is generically sweet, but in the mouth it is instantly and aggressively green. The product page notes that the leaves are from Bulang, and I can believe it, because this tea is heavy going. It isn't punchy, clean, and fresh, like the 2009 Nadacha "Bulang Qiaomu", instead being the brutal harshness of the plantation. It's raw, and it hurts the throat.

There is a sweet, grain character that was in the dry aroma, but not too much else. It reminds me of regular production Xiaguan, rather than their specials. At $23, it isn't too expensive, and Puerh Shop deserves credit for that.

Is it good for aging? Well, it is brutally astringent. If you believe that's what ages well, then go for it. I tend to look for some content and complexity underneath the brutal power, and this tea just seems too raw, too rough, too nasty, and with too few other contents.

After five infusions at home, I tire of its one-dimensional agony, and take the remainder to work where it serves as a low-maintenance background tea. Thanks to GV for passing this one on to me, as it's nice to sample from all ends of the spectrum.

Remember the "Rule of Menghai" and you won't go far wrong!

Is it good for aging? Well, it is brutally astringent. If you believe that's what ages well, then go for it. I tend to look for some content and complexity underneath the brutal power, and this tea just seems too raw, too rough, too nasty, and with too few other contents.

After five infusions at home, I tire of its one-dimensional agony, and take the remainder to work where it serves as a low-maintenance background tea. Thanks to GV for passing this one on to me, as it's nice to sample from all ends of the spectrum.

Remember the "Rule of Menghai" and you won't go far wrong!