Attitudes to food and drink vary geographically, and according to socio-demographic groups - typically education level, in OECD countries. I think it is fair to say that awareness of the benefits of eating healthily is becoming more widespread. Most tea drinkers, for example, have some sense of looking for good products, and in avoiding the consumption of additives that might be unhealthy.

This desire to "eat well" is mixed up in a whole heap of social and cultural complications. In the US (and, increasingly, in the UK), the general public seems to be hooked on "low quality" foods. I cannot speak for other countries, but in England, in which I hold a personal interest, recent studies have shown that this tendency to consume "lower quality" food and drink is most prevelant in low-income, low-education level populations. Consequently, higher rates of obesity, hypertension, and lower life-expectancy are associated with these groups. Those groups with "stressed income" are especially likely to be malnourished and consume fast food, as reported in a recent OECD study.

In the UK, and perhaps in other Western countries, our ability to detect unhealthy ingredients in food may be diminished by a diet already heavy in pesticides, fertilisers, preservatives, colourings, and flavourings. I cannot imagine that someone who has been raised on pizza and fried foods would be particularly sensitive to the presence of small quantities of pesticide in their tea, for example.

In the UK, and perhaps in other Western countries, our ability to detect unhealthy ingredients in food may be diminished by a diet already heavy in pesticides, fertilisers, preservatives, colourings, and flavourings. I cannot imagine that someone who has been raised on pizza and fried foods would be particularly sensitive to the presence of small quantities of pesticide in their tea, for example.

In China, the effect is different: culturally, the Chinese prefer "whole food" products, prepared by hand. The average Chinese has a rightful disdain for the diets of Westerners. It is not by accident that the majority of Chinese seek out Chinese food when they are abroad. I have seen, time and time again, visitors from China entirely revolted by Western food.

However, this effect in Chinese from the Mainland is complicated by the fact that their food, water, and air are poisoned - sometimes literally. Most of my Chinese friends who still live in China are now unable to detect the presence or absence of additives in their food, such is the ubiquity of pollution and agrochemicals. Indeed, "food safety" came just under "water safety" and "corrupt officials" in a recent (official PRC) survey of popular opinion, reported in The Economist. My wife refuses to let our sons travel to the Mainland until they are five years old. My wife's family regularly recounts the latest food-safety scandal to effect everything from rice to garlic. Only the largest, child-killing scandals such as Sanlu's milk poisoning tend to be reported internationally.

So, I maintain, whether in the West or the East, for different reasons, there are factors that serve to prevent some of us being able to distinguish the presence of pesticides and fertilisers.

However, this effect in Chinese from the Mainland is complicated by the fact that their food, water, and air are poisoned - sometimes literally. Most of my Chinese friends who still live in China are now unable to detect the presence or absence of additives in their food, such is the ubiquity of pollution and agrochemicals. Indeed, "food safety" came just under "water safety" and "corrupt officials" in a recent (official PRC) survey of popular opinion, reported in The Economist. My wife refuses to let our sons travel to the Mainland until they are five years old. My wife's family regularly recounts the latest food-safety scandal to effect everything from rice to garlic. Only the largest, child-killing scandals such as Sanlu's milk poisoning tend to be reported internationally.

So, I maintain, whether in the West or the East, for different reasons, there are factors that serve to prevent some of us being able to distinguish the presence of pesticides and fertilisers.

Perhaps it might be useful to contribute my own standing at this point: I am not a "health freak". I was, however, raised in the countryside, with a robust diet of home-cooked whole food, and in an area with minimal pollution. As a student, I spent a good decade abusing my body with all manner of the usual student libations. As a father and a professional, now in my thirties, I am back to my usual diet of "straightforward living", kept on the straight-and-narrow by the kindly ministrations of my dear (Chinese) wife, which keeps the quantity of additives in my diet to a minimum.

Additionally, there is a genetic trait in my family that predisposes us (all men, oddly enough) to sensitivity to most allergens. I inherited this from my father, who was a colonial British growing up in Zambia and Kenya; in turn, I have passed this sensitivity onto my youngest son, Xiaolong, who has my white skin, allergies to most things, and eczema. (It skipped my eldest son, Xiaohu, as he seems to take after his mother, having her Chinese skin and a lack of allergies.)

This combination of (relatively) "straightforward living", a clean environment, and a sensivity to allergens makes me quite sensitive to the presence of agrochemicals in tea.

Additionally, there is a genetic trait in my family that predisposes us (all men, oddly enough) to sensitivity to most allergens. I inherited this from my father, who was a colonial British growing up in Zambia and Kenya; in turn, I have passed this sensitivity onto my youngest son, Xiaolong, who has my white skin, allergies to most things, and eczema. (It skipped my eldest son, Xiaohu, as he seems to take after his mother, having her Chinese skin and a lack of allergies.)

This combination of (relatively) "straightforward living", a clean environment, and a sensivity to allergens makes me quite sensitive to the presence of agrochemicals in tea.

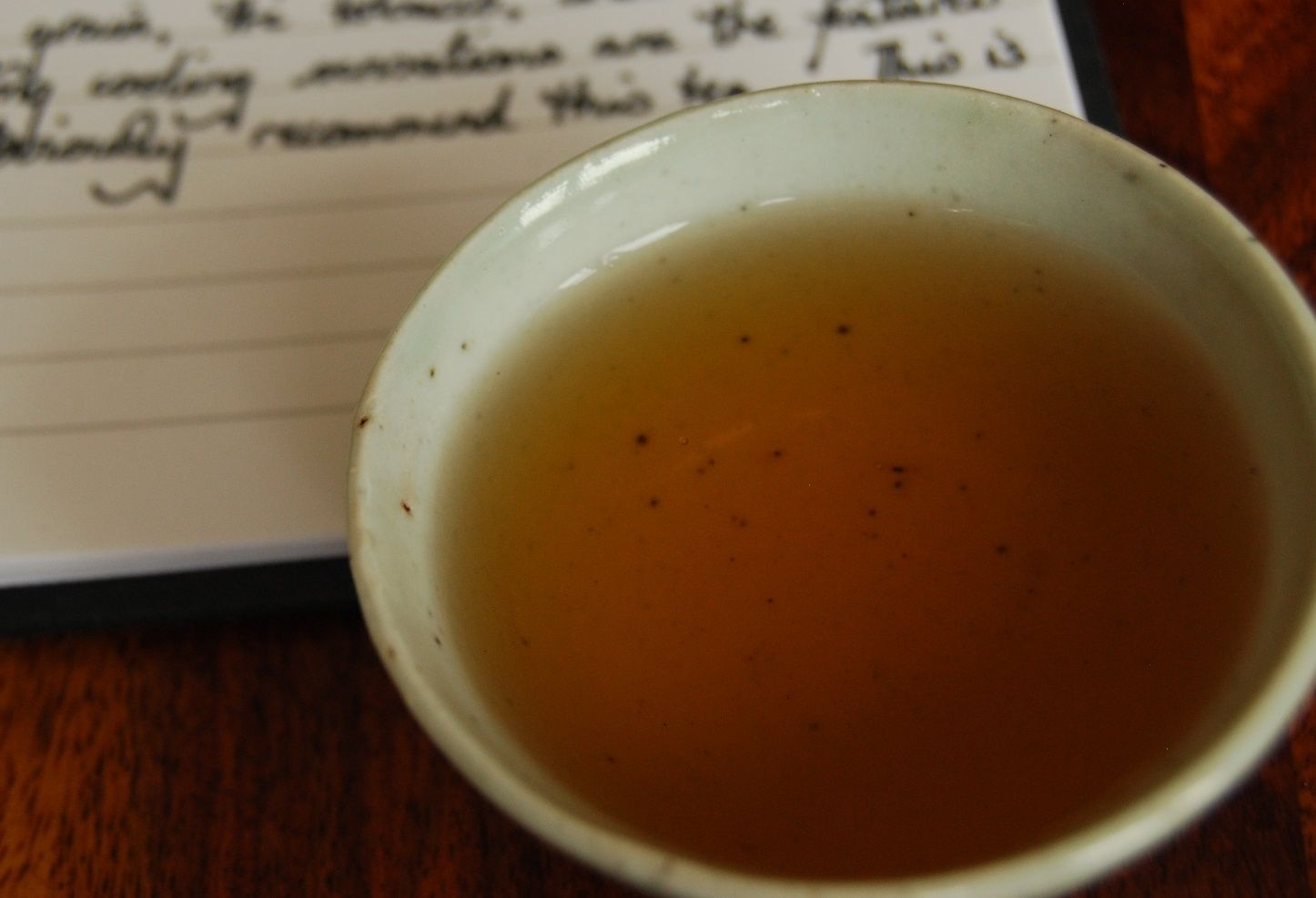

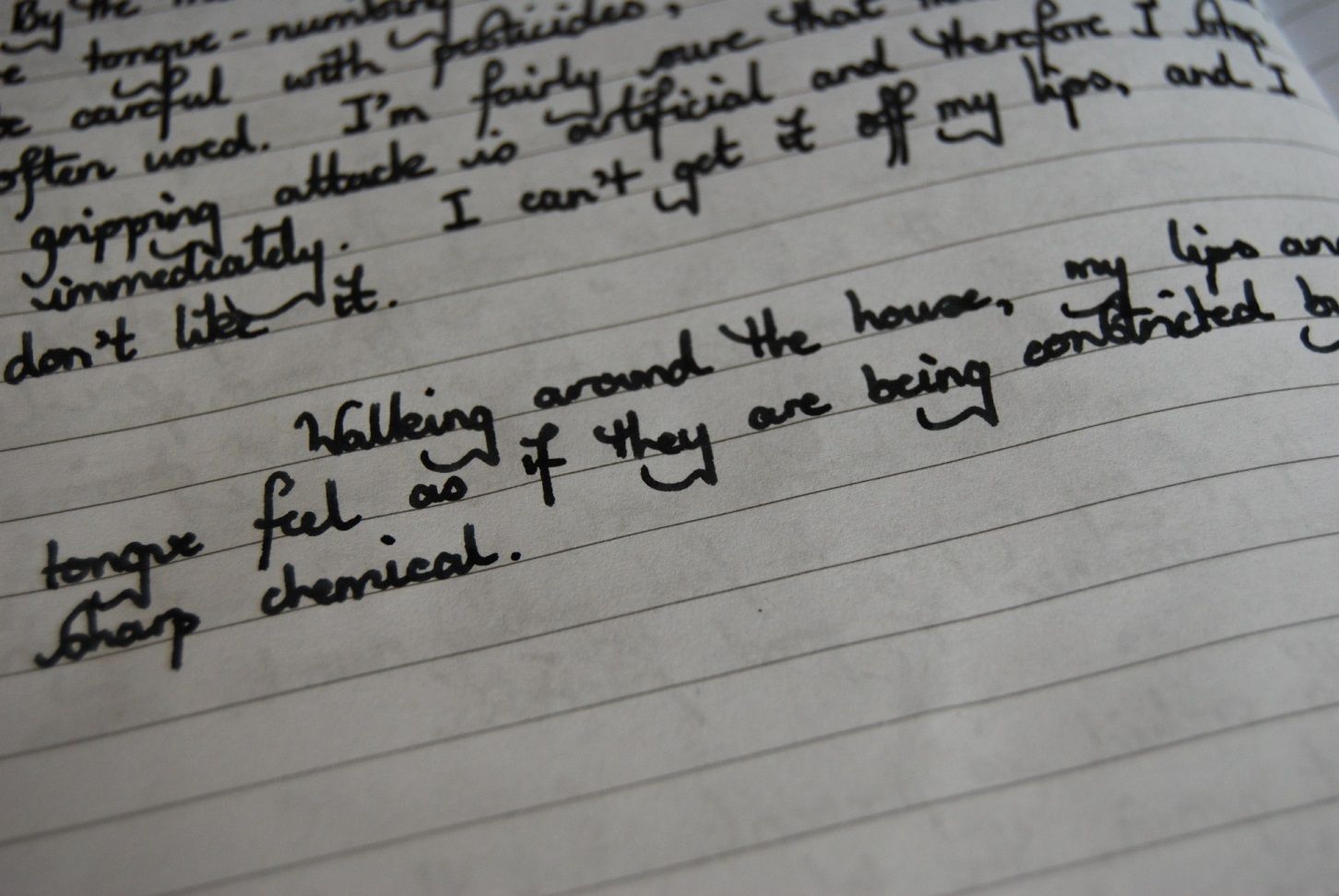

Shown in the first three images for this article is a cake that I tried recently which was remarkable. It actually tasted like "good tea", in terms of its leaves, but the very first sip filled my mouth with a cloying, freezing sensation that reminded me of getting old-fashioned hairspray in my mouth (of the kind that my grandmother used). My lips felt as if they were being constricted; the tip of my tongue throbbed; the sensation stuck tight to the sides of my mouth. I rinsed my mouth several times, and, despite trying to shift the sensation throughout the day, it lasted many hours - even later, when I went to work in my lab.

It turned out, following a later lab test performed in light of my suspicions, that the tea contained a number of pesticides, in quantities between 10% and 78% of those permitted by the EU regulations to be present in tea. These are the "MRL"s, or maximum residue levels, and which are typically more strict in the EU than in, for example, the USA. That is, the tea was "legal", the pesticides were within limits, but they were entirely obvious and absolutely negative in their effect.

It turned out, following a later lab test performed in light of my suspicions, that the tea contained a number of pesticides, in quantities between 10% and 78% of those permitted by the EU regulations to be present in tea. These are the "MRL"s, or maximum residue levels, and which are typically more strict in the EU than in, for example, the USA. That is, the tea was "legal", the pesticides were within limits, but they were entirely obvious and absolutely negative in their effect.

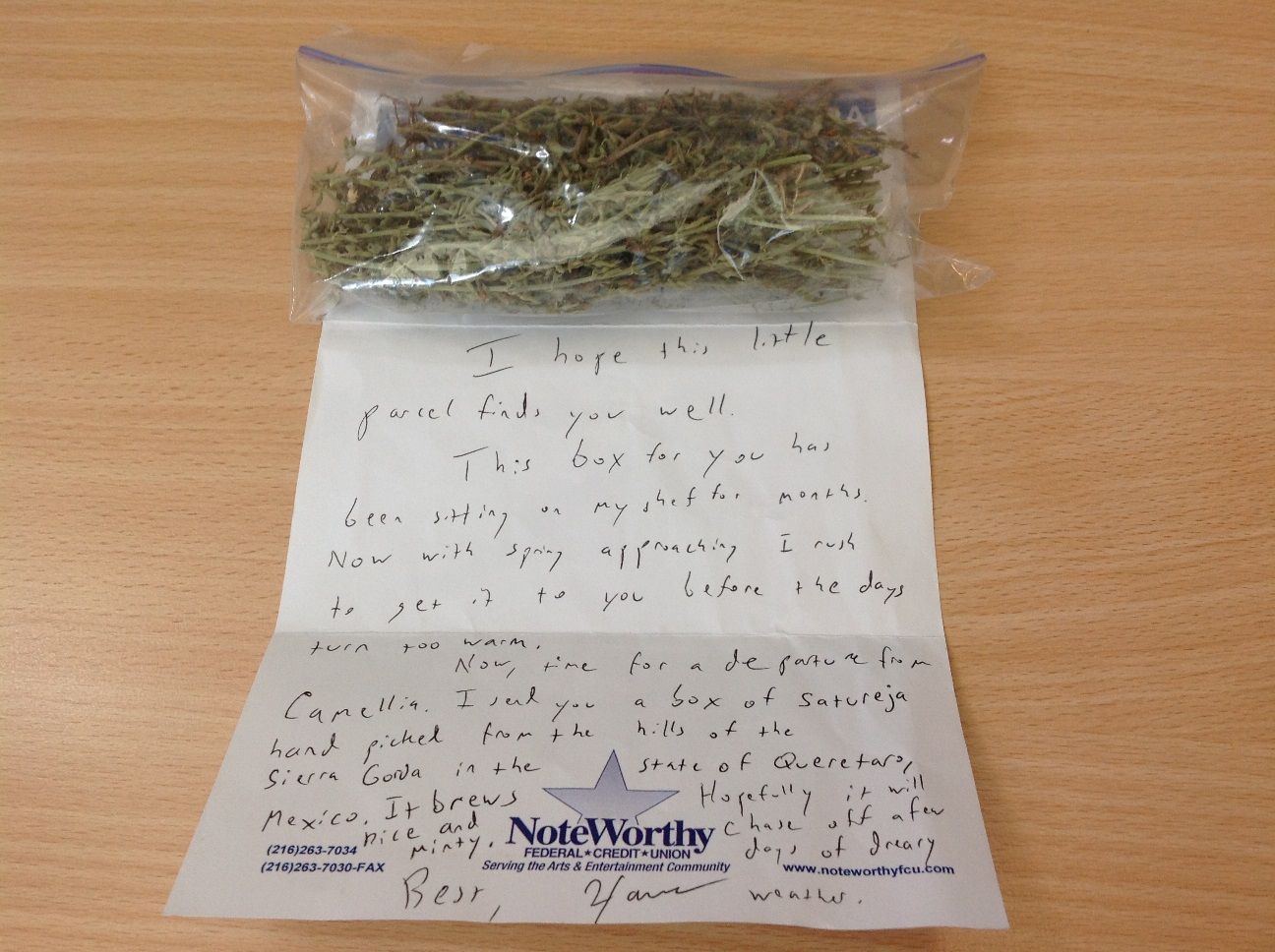

Shown also in this article is the "pesticide tasting sample" from Essence of Tea, which Mr. Essence kindly sent to me, and which may be bought from his web-site. The accompanying lab report shows that the tea is 2013 Zhenyuan pu'ercha, and that it contains omethoate at 0.02 mg/kg, where the EU limit (MRL) is 0.05 mg/kg. Again, this is "legal" tea... (I am happy with the £15 price for the tasting set, because the lab test is expensive.)

You can see from the above photograph that this is maocha. When taken as a whole, in the large sample bag, I can smell only a dense fruitiness. However, when turned out into the gaiwan, the leaves have a background scent reminiscent of sour nicotein.

You can see from the above photograph that this is maocha. When taken as a whole, in the large sample bag, I can smell only a dense fruitiness. However, when turned out into the gaiwan, the leaves have a background scent reminiscent of sour nicotein.

The rinse, pictured above, generated a definite scum. While many teas have saponins that, my definition, result in soapy bubbles, they are quite different to "scum".

The persistence of this clinging scum is apparent from the photograph below - the scum does not rinse off, preferring to cling to the glazed lid unlike saponin-froth, and which requires a cloth and some actual manual scrubbing to remove.

The persistence of this clinging scum is apparent from the photograph below - the scum does not rinse off, preferring to cling to the glazed lid unlike saponin-froth, and which requires a cloth and some actual manual scrubbing to remove.

Even after the first infusion, noting that the tea has already been rinsed (with long duration), some of this scum remains, and gets caught in the filter that I use to strain leaves from the soup before they hit the gongdaobei [fairness cup]. This is highly unusual - most teas at this stage, even if they have saponin-froth, are clean by the first infusion.

The resulting soup has no real scent. The first sip slams into the lips and tongue just like the hairspray-effect of the cake described previously. It adheres to the lips and cheeks, freezes and numbs, and constricts in exactly the same way. It is this tightening and drying of the tissue that is particularly obvious.

After that single (perhaps 5ml) sip, I discard the result of the brew and wash the teaware with soup and water.

After that single (perhaps 5ml) sip, I discard the result of the brew and wash the teaware with soup and water.

Note that both of the teas that I described in today's article were legal, even by strict EU standards. A recent Greenpeace report (from 2012) described the random sampling of a number of mainstream Chinese teas, the majority of which were found to contain pesticides, a large number of which were found to contain pesticides banned by the PRC (but which were legal in the EU, oddly). Amusingly, one of those latter pesticides turned up in the lab report of the first cake that I described.

So, the big question: what are we to do?

One extreme reaction is to swear that we will never drink anything that has come from the Mainland. For example, we might drink hand-picked Mexican herbs that look very much like narcotics, as pictured above (thanks to HC - how that got through customs I will never know!).

We just have to be sensible. A more realistic solution is to exercise some sensible quantity of discrimination. Depending on your existing diet, environment, and exposure, you may be more or less sensitive to the effects that were entirely, lip-searingly obvious in the samples described in this article. Have a crack at the Essence of Tea sample, and see how you get on. Just don't use your favourite zisha teapot.

As for me, I make it a rule to avoid Mainland green and red teas (lucha, hongcha), as the use of agrochemicals in such crops is ubiquitous. My tastes prefer pu'ercha, where, fortunately, the use of such chemicals is not guaranteed.

If one were to maximise one's chances of buying pu'ercha that contained pesticides, it would be through buying modern tea (probably 2006+, including the pu'ercha bubble of 2006 when yields increased dramatically) and buying from low-quality labels (CNNP, Haiwan, etc.). However, the use of pesticides is not limited by year, quality of label, or quality of leaf. Just because a tea is old, or "gushu", or made from a vendor you like, does not mean that the cake is immune from a farmer contributing a rogue batch to the mixture.

Ultimately, we must train ourselves to be able to discern the good from the bad. An important part of that process is sharing our findings with others. So, for the good of the many: keep writing, tea-writers.

For completeness, I have updated my notes for the 2012 Bulangshan from Essence of Tea, which forms the "without pesticide" sample in this set.

So, the big question: what are we to do?

One extreme reaction is to swear that we will never drink anything that has come from the Mainland. For example, we might drink hand-picked Mexican herbs that look very much like narcotics, as pictured above (thanks to HC - how that got through customs I will never know!).

We just have to be sensible. A more realistic solution is to exercise some sensible quantity of discrimination. Depending on your existing diet, environment, and exposure, you may be more or less sensitive to the effects that were entirely, lip-searingly obvious in the samples described in this article. Have a crack at the Essence of Tea sample, and see how you get on. Just don't use your favourite zisha teapot.

As for me, I make it a rule to avoid Mainland green and red teas (lucha, hongcha), as the use of agrochemicals in such crops is ubiquitous. My tastes prefer pu'ercha, where, fortunately, the use of such chemicals is not guaranteed.

If one were to maximise one's chances of buying pu'ercha that contained pesticides, it would be through buying modern tea (probably 2006+, including the pu'ercha bubble of 2006 when yields increased dramatically) and buying from low-quality labels (CNNP, Haiwan, etc.). However, the use of pesticides is not limited by year, quality of label, or quality of leaf. Just because a tea is old, or "gushu", or made from a vendor you like, does not mean that the cake is immune from a farmer contributing a rogue batch to the mixture.

Ultimately, we must train ourselves to be able to discern the good from the bad. An important part of that process is sharing our findings with others. So, for the good of the many: keep writing, tea-writers.

For completeness, I have updated my notes for the 2012 Bulangshan from Essence of Tea, which forms the "without pesticide" sample in this set.

The Greenpeace report was poorly done. Anyone who is familiar with analytical chemistry will notice the lack of measurement error which is rather critical for data like this. Their heart was in the right place, but poor execution by whoever was in charge.

ReplyDeleteAs far as the bad stuff in tea goes don't forget there are lots of things that are really bad for you that humans can't detect with senses regardless of how ideal your diet is.

This is always an interesting topic but testing is difficult with all the producers of the good stuff making rather small batches. It seems hard to justify by the retailer for the increased cost for what might be mediocre product. Tangentially related, the overwhelming majority of "organic" teas I have had were not good.

Interesting article David. The issue of pesticides is, I think, more widespread than most people are aware.

ReplyDeleteYour notes concerning the scum on the surface of the brewed tea are interesting also. I hadn't noticed it in this sample before. I'm not sure how related this is to the pesticide residue detected on the tea. There are many teas which display signs of agrochemicals when drunk that don't have this froth. I'll have to keep an eye out for it in future, but I don't think that its absence could be used to infer the absence of agrochemicals.

Good luck scraping your tongue clean!

p.s. I'm wondering why you left Dayi out of your list of tea companies. As far as I'm aware the use of agrochemicals is pretty much to be taken for granted in plantation teas. The high intensity, monoculture environment almost necessitates the use of fertiliser and pesticides. And, as we've seen from this sample - these levels of pesticide are entirely legal.

ReplyDeleteThere's a reason that they occasionally press an 'organic' tea... most of it is not.

Dear Brad,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the reply. A quick response before my day kicks off (!):

1. The Greenpeace report simply summarises the usual MRL tests. (Bear in mind their expected readership.) The tolerances on these tests are, to my knowledge, standardised under the EC testing compliance framework, and are consequently straightforward to determine. In most EC-compliant tests, tolerance is below 0.01 mg/kg across the board. The conclusions are unaffected: the presence of methomyl is above test sensitivity (0.01 mg/kg) - sometimes, far in excess of MRL. I don't imagine that Greenpeace are going for a peer reviewed publication. ;)

2. Detectable toxins form a subset of all toxins, certainly. I can't imagine that anyone would claim that a product is guaranteed "clean" merely because they cannot detect something with their own personal tasting apparatus.

3. "Organic" wine, cheese, and tea are usually horrid, I agree.

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Dear David,

ReplyDeleteA likewise quick response, if I may:

1. Scum implies pesticide, but lack of scum does not imply lack of pesticide. As a former computer scientist, you will be familiar with the rule of propositional logic, modus tollens: if "scum implies pesticide" and we observe "no pesticide", all we can conclude is "no scum". Sequent: we cannot logically conclude that "no scum" implies "no pesticide". //

2. Dayi is plantation tea, and certainly falls within my ellipsis after "Haiwan". :)

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

You know you might have something on the scum.. I never really thought about it until now. I remember a tea shop that had a brief life here in Denver, CO (it has closed its doors as of now and shall remain nameless). They had some good teas but most were horribly overpriced teas and of low quality. The last tea I bought from them was a loose leaf Pu'Erh that created a scum like that in your photo. Not only that but it had an overwhelming (at least to me.. others that tried it couldn't taste the off flavors) chemical taste to it. It also tasted as though it had been dried out next to a highway.. there was a strong petrol flavor.. it was horrid. I ended up giving the tea away to someone who couldn't discern the off flavors and smells. I also never shopped from that tea store again. We really don't have a lot of good local tea stores in Denver, CO USA sadly.

ReplyDeleteOn that note I wonder if a sensitivity to allergens somehow makes you more able to detect these off flavors and scents? I know myself at least when I was growing up had a multitude of allergic sensitivities which were immediate and usually debilitating. I have strangely completely grown out of them as an adult. I am now as healthy as an ox but I have retained my extreme hypersensitivity to smells and tastes.

Dear Hobbes,

ReplyDeleteI agree completely with your logic, at least with the negative side of it. With the positive side, it's certainly a possibility, and a very interesting hypothesis - I'm going to have to keep an eye out for it. As Mighty Tea Monster noted above, you may very well be on to something!

best wishes,

David

Dear Tea Monster,

ReplyDeleteYou might right; my situation was the same as yours - like many with a childhood genetic predisposition to allergen sensivity, I grew out of it during adolescence. Thankfully! However, while the presence of such allergens no longer provokes the inflammatory response from the immune system (blocked nose, itching eyes, etc.), it seems reasonable to suggest that the senses would not lose their ability to detect that which was previously so aggressively rejected by the immune system. An interesting hypothesis!

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Dear David,

ReplyDeleteAs with all logical hypotheses, they merely exist as possibilities with which we might explain the observations - I am always on the look-out for (and welcome!) data that force me to re-evaluate my hypotheses in light of those new data. :)

Certainly, my scummiest teas have turned out to be rough ol' plantation teas, so far!

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

A good scientist 'till the end Hobbes :)

ReplyDeleteWell, a scientist, at least ;)

ReplyDelete... and modest too ;)

ReplyDeleteA chemist friend of mine mentioned pesticides are not water soluble.. otherwise they would be washed away every time it rains, so unless you are eating the tea leaves you probably won't ingest any pesticides.

ReplyDeleteYour article intrigued me, Hobbes. I bit the bullet and purchased the sampling pack to see if I can tell the difference.

ReplyDeleteAlso, I'm finding all of my 'organic' puerh samples and trying them out next to ones that i'm sure have pesticides. So far, I'm having a little trouble telling the difference, but there definitely is some with some teas i've tried.

Best,

Bryan

Interesting about the scum and your mention of not drinking hongcha. I recently ordered a small amount of Dien Hong because I'd yet to drink Chinese red tea and I found it extremely scummy. I thought it might be to do with the hairy tips, but now I'm thinking otherwise...

ReplyDeletephoto of the scum:

http://bengivenni.smugmug.com/TheDragonsWell/Golden-Tips-Red-Tea-Dien/i-xfPRFFb/A

PS Do you know whether rinsing the tea does away with most of the pesticides or would that be wishful thinking?

ReplyDeleteFrom what I understand, any pesticides on the surface of the leaf would form a mechanical mixture with the water in the first rinse since they are not water soluble. Any pesticides already incorporated into the leaf cells would be ingested if you ate the leaf.

ReplyDeleteLet's think about the nature of pesticides. An anomyous poster (!) further up quotes a "chemist friend" as noting that pesticides are not soluble in water (which is correct).

ReplyDeleteThis was then used as an axiom to conclude that, unless one eats the leaf, no pesticide will be ingested.

With the greatest respect, we must learn to reason for ourselves. The case as presented is argumentum ad auctoritatem, a casual appeal to authority, which is the root of lazy thinking and needs to be promptly addressed before it becomes a dangerous habit.

Let's have a slightly closer look. While it is true that pesticides are water-insoluble, to then directly conclude that consumption can only occur by ingestion of the leaf fails as an argument.

We can imagine a similar proposition; given that most people are unfamiliar with the nature of (the vastly disparate groups of unrelated chemical families that comprise) pesticides, let us imagine a compound that is insoluble in water, but which adheres to the plant, as would be anticipated with an effective pesticide. Imagine, for one of many possible examples, that it were an "oily" substance, which obeys our two requirements, and has the advantage of being a substance the properties of which are familiar to the layman (although the majority of pesticides are not actually oleaginous). Imagine, then, that we take the leaves and subject them to continuous brewing in water that is boiling. There are many compounds released from the interior of the leaf under such conditions that are not released during exposure with rain - it is this effect, after all, that allows us to enjoy tea. The insoluble, plant-adherent substance, under such conditions, form the "mechanical mixture" to which Adam rightly refers. The result is the additive not in solution, but in mixture.

It is not hard to identify other observations that prove the fallacy that an insoluble compound sprayed on a leaf can only be consumed by ingestion of that leaf, even after considering the change in temperature of the water during infusion. The very considerable environmental damage from run-off pesticides (and fertilisers) is a regularly-cited example of the insoluble nature of a pesticide being taken up in mixture, which then accumulates in other ecosystems and causes harm. (A good example that is taught to eight-year-olds in primary schools in the UK, for example, is that of eutrophication.) A second example might be the existence of "Maximum Residue Levels" (MRLs) and other equivalents outside the EU, which are quoted for non-ingested substances, one of which is tea.

The world is a complex place, and resorting to "my chemist friend told me so" is a friendly warning that we should be engaging our own faculties of reason. Keep an open mind. It's possible, just possible, that those people around you who claim to be able to detect pesticides using their senses may, actually, be correct, and not barking mad. You would certainly do well to offer them the respect of considering their argument.

With very best wishes, and toodlepip,

Hobbes

Dear Jidao,

ReplyDeleteNote that all of the teas described in my article were rinsed, and that the "pesticide" sampler from EoT was rinsed for a long time. If you accept that the stringent effect experienced in my mouth was due to the presence of pesticide, then it seems reasonable to conclude that the rinse doesn't shift it. :)

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Thank you. Now I'm hoping that I haven't seasoned my zisha pots with pesticides!

ReplyDeleteI wonder also if some gushu trees, which may have be very old and largely untouched until recent demand for them caused increased production, and potentially, subjected them to pesticides at an attempt to increase yield; and thus, another potential example of where gush does not equal pure or pesticide free. I wonder if they might even have the capacity to retain more pesticides to their age and depth of being rooted in the soil, compared to a younger plantation bush.

ReplyDeleteIf a tea generates scum and a sensitive nose finds something to be off, then that is enough evidence for me to pass over that particular tea!

ReplyDeleteI just realized chemist has different meanings in Europe vs North America. Where I live it refers to a professional with a degree in chemistry. These are people who do quantitative tests and measure the amounts of various chemicals in solutions on a regular basis. My "chemist friend" is telling me a weak acidic solution is the only sure way to remove pesticides from fruits and vegetables. Tea leaves have the same cellular structure. I sincerely hope none of us ingest pesticides through normal tea brewing. I am certainly not brewing my tea with a solution of water and vinegar!

If pesticides are water-insoluble, in order for them to be effective, don't they have to be at least liposoluble? As far as I know, because of the structure of our cell membrane (I don't know about insects,but at least in humans it is that way), liposoluble compounds are able to penetrate the cell membrane much better. Therefore, you would be not only ingesting the chemicals just by drinking the tea, but they would also have their "desired" effect on your body.

ReplyDeleteEven if you don't ingest the leaves themselves, these compounds will be, to some degree, washed into the tea you drink just by brewing the leaves. (you can wash away oil with enough hot water without it dissolving in the water -> therefore, the "oil" will be in your tea)

Since, for example, neonicotinoids are a class of pesticides that act as neurotoxins, I can assume they are liposoluble and therefore they pass the cell membrane. (even if illegal in China, they were being used before the patent on the product expired)

So the argument that you have to eat the leaves does not stand, imo.

Apologies for this late comment. Interesting blog and

ReplyDeleteinteresting reading (the one above). Although I

sometimes do not agree with your opinions about certain teas, certainly you are doing a great job.

Besides pesticides, here are a couple of extra reasons for concern for puerh drinkers like us:

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10942912.2014.885043#.VMCegy6UcZN

http://www.lifescienceglobal.com/pms/index.php/jbas/article/view/2217

I am not particularly fan of humidity, as you seem to be. If the above results on aflatoxin are confirmed by further research, it may mean that we are all playing a strange version of the Russian roulette...

Regards from the dark side!

Thanks for the links, Xiao Bai. A bit worrying for a lover of ripe puer such as myself.

ReplyDeleteTea Classico claims to conduct tests on all their aged puer teas (http://www.teaclassico.com/index.php?route=blog/article&article_id=4), which is a good thing. But if this is also a problem for ripe puer, I wish they would conduct similar tests for those. Is it even possible to make "safe" ripe tea, considering the process it undergoes? I sure hope so.

Caro Scholardilettante,

ReplyDeleteI would not trust much what Tea Classico claims. Mr. Aliev is just a middle man for a Taiwanese vendor, who keeps his puerh in extremely humid conditions (I know well this vendor because he sold me an aged tuo that triggered a serious allergic reaction, which forced me to throw away most of it. Yet, Mr. Aliev never agreed to provide me with his address so I could send him a sample to back up my claims about the sorry state of his products).

Thus, whatever Mr. Aliev claims about the aflatoxin content in his teas is only second hand information and I would be very cautious because I know first hand (I live in Taiwan), that conditions in many puerh warehouses here can be very unhygienic.

An interesting document from the FAO that addresses the issue of pestcides being in the liquor once infused or not: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/est/meetings/tea_may14/ISM-14-3-Brew_Policy.pdf

ReplyDelete