I'm in Viking country for the next five days: Harrogate, near York, in the dim and distant north of England. I'm not sure why a conference would be held here, but it's very pretty and so I won't ask. It always amuses my American colleagues when I mumble about travelling five hours to get to the other end of the country - it really must seem tiny to North Americans.

Before I left, I thought it wise to dip into my sample of this tea.

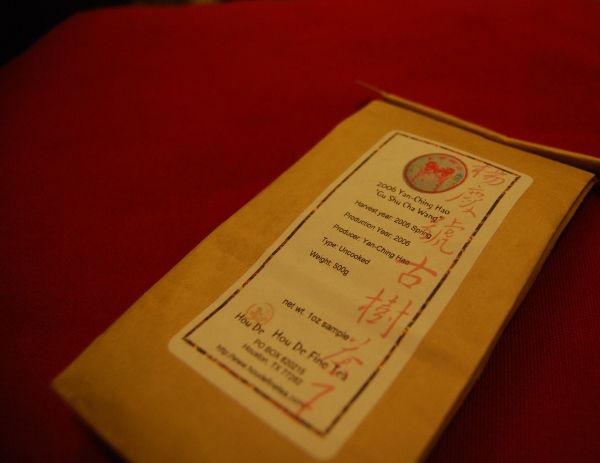

Marketed variously under "Yanching Hao" and "Yangching Hao" by

Houde (I've used Pinyin: Yangqinghao), from whence cometh this sample, this tea claims "gushu" [ancient tree] status, and the even more nebulous "chawang" [tea king].

Comprised of maocha from the "six famous tea mountains" with an estimated 30% gushu leaves, I wonder if a claret producer would be allowed to name their wine "Margeaux" if it were less than 1/3rd proper grapes, with the other 2/3rds coming from "France". AOC/DOC enthusiasts have their eyes on the future for increased Chinese naming and quality regulations.

It is pertinent to note, in the assessment of this tea, that it is priced at the Xizihao and Chen-Guanghe Tang level (i.e., very high). A previous issue of the Chinese periodical "Pu'er Teapot" featured this cake on the front cover.

~10cl Caledonian Springs @ 100C in 20cl shengpu pot; ~5 leaf; 1 rinse

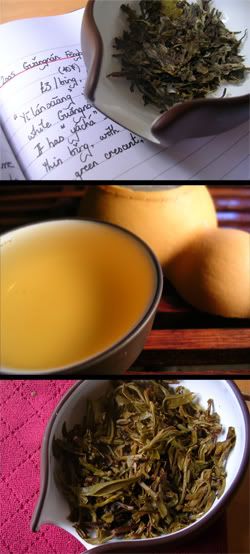

Dry leaves:

Quite an assortment [pictured]: some very dark, some green, some mid-brown, some silver tips, some stems, with something from all grades. The aroma is very high and sweet, and the scent rather appeals to me.

3s, 5s, 7s, 10s, 12s, 15s, 20s:

From the infusion times, you might wonder if this tea is a bit weak, given that most one-year-old cakes are potent to the degree that infusion times must be kept low, often staying at 3-5s even out to the sixth infusion and beyond.

First impressions begin, as ever, with the beidixiang, which is thin but sweet. It gives way to a decent, sugary lengxiang. The impression of weakness continues with the colour, which is a thin yellow, and continues with the flavour: gentle, grape-like, a touch of straw, and very little ku [bitterness].

This tea is gentle, clearly aimed at the "drink it now" crowd. This isn't a bad goal, but it does require that it is backed up with enough flavour to make it worthwhile. This cake is enjoyable, light, but ultimately forgettable. It has to be pushed on in its brewing to get any character out of it, and never becomes strong.

The confusion in the blend becomes apparent in later infusions: a little mushroom appears, but fades by the sixth infusion, by which time the aroma has long since vanished. The texture of the tea is fine, but thin, which rather sums up the cake for me.

Wet leaves:

As you can see, they are as random as we saw in the dry leaves, covering all types and genres.

Overall:

A true "jack of all trades, and master of none". It is pleasant enough, in its simple way, but woefully underpowered.

To put it in engineering terms, this tea is like a vector sum, in which each component is pointed in a different direction, the net effect of which is a near-zero equilibrium. The blend includes too many different characteristics, none of which are solid enough to satisfy, excepting a generic sweetness.

This is the risk of blending: a favourable present may be created, but the cracks in the blend soon show through, as the various weak components fail one by one, leaving an unfulfilling tea.

It is not clear to me that appearing on the front cover of a tea magazine justifies such a high price, and promotion to the big leagues. This tea reminds me of the

Chen Guanghe Tang in its contrivance to be pleasant and enjoyable, yet perhaps lacking the ability to satisfy.

Addendum

March, 2011

This currently costs $135 at

Houde, which many of us originally wrote off as being far too expensive. Looking over my original notes, I didn't enjoy this tea very much - I found weakness, no bitterness at all, and thought it too light to age well.

Yangqinghao means "Yang [family name] celebration brand"

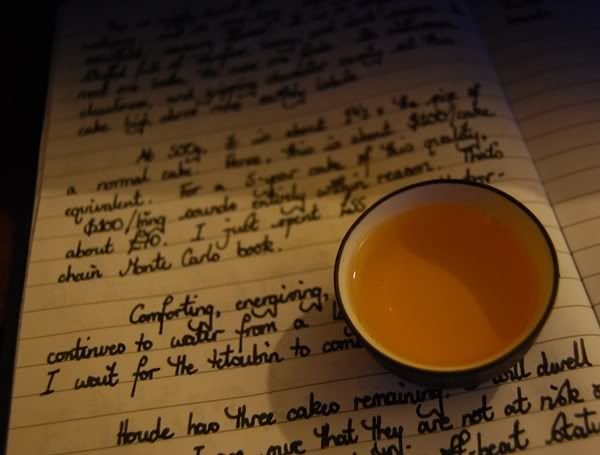

The leaves are beautiful, and, as the potent, pungent aroma of spring leaves fills the room upon opening the packet, I am ready to be proven wrong, and to be impressed. The sheer power of the aroma really is genuinely surprising, and the pre-dawn darkness suddenly seems a lot more welcoming.

Good leaves - pretty and very long

In the aroma cup, similarly, the scent is a knock-out. Heavy, dark sugars that last seemingly forever - I am already rethinking my attitude to this cake, and looking very carefully at the asking price.

The soup is yellow-brown, turning orange in the air

Gripping and mouth-watering, there seems to be plenty going on in this tea. It holds my interest very well - the more one looks, the more one finds. Heavy camphor, honey, dark sugars.

Its endurance and cleanliness are remarkable, as is the resounding kuwei [good bitterness] in the throat. How I previously concluded that this cake was weak and light seems odd, in light of its obvious power.

Comforting, energising, uplifting - my mouth continues to water from a long-past swallow as I wait for the tetsubin to boil a new batch of water.

Strong, whole leaves, all of a similar level of oxidation, with minimal monkey business

As the infusions wear on, the previous glories become more prosaic: it has a big, flat base of green plantation that, while never rough, does detract from the original spring-time complexities.

After the third infusion, I was resolved to buy a few cakes (they are a stonking 500g); after the sixth infusion, I was down to buying just one cake; after the ninth infusion, I was uncertain whether to buy one at all.

The $135 price-tag is £100 - for that money, I could buy another

1997 Henglichang "Bulang", which is about twice as good as this Yangqinghao. Therefore, I simply cannot justify spending that money on this inferior (though still very decent) cake. If this were priced around the $80, it would be more appropriate, in comparison to the rest of the (Western-oriented) tea market.

Nonetheless, it's fascinating to see how two sittings, spaced four years apart, can result in very different conclusions of the same pu'ercha.

In a world of mostly-dodgy cakes, where everyone seems to concentrate on single-mountain productions, it's heartening to see an unashamedly eclectic blend of maocha from multiple regions. Blending is quite a skill, and the resultant cakes can often be greater than the sum of their parts.

First up is the veracity of its claim to age. Regular readers might remember the Maguan Panguwang bing that Lei bought in quantity to fulfil her daily shupu drinking. Tea Logic's VL pointed out that the wrapper was reminiscent of the style that became popular in 1999 - recalling that the tea vendor in Lei's hometown claimed he purchased it in 1997. Going solely on the characteristics of the tea, my impression is of something in excess of 7 years (of which we have a fair number of examples). Given also that the vendor is (as I understand) a trustworthy friend of the family, the scales tip in his favour. Perhaps it is unimportant, given the pleasing outcome of the tea (and it's price that asymptotically approaches zero).

First up is the veracity of its claim to age. Regular readers might remember the Maguan Panguwang bing that Lei bought in quantity to fulfil her daily shupu drinking. Tea Logic's VL pointed out that the wrapper was reminiscent of the style that became popular in 1999 - recalling that the tea vendor in Lei's hometown claimed he purchased it in 1997. Going solely on the characteristics of the tea, my impression is of something in excess of 7 years (of which we have a fair number of examples). Given also that the vendor is (as I understand) a trustworthy friend of the family, the scales tip in his favour. Perhaps it is unimportant, given the pleasing outcome of the tea (and it's price that asymptotically approaches zero). Dry leaf:

Dry leaf: