So-called "Zen learning" is something that fascinates me, and it's something that we're all undertaking when we brew tea.

I've twice before mentioned Herrigel's Zen and the Art of Archery, which brought Zen to Europe after World War II. In this short classic, Prof. Herrigel described how he learned archery from one of Japan's masters in the art: day after day, month after month, he repeated the tedious exercise of holding the bow sideways, and then simply drawing and releasing the bow. With no arrows. Draw, release, draw, release. Day after day.

After some months, the master commented after one drawing-and-releasing, "There! You had it!" He had observed something transcendent in the manner in which Herrigel released the bow-string, at exactly the right moment, and with exactly the right quality. Herrigel duly tried to repeat the success, with excitement, but met with more familiar failures. His master told him to continue the exercise.

Fighting tedium and doubt, more months passed. Every now and again, the master would note a drawing-and-releasing in which he observed that certain quality. Over time, these incidences ("successes") became more frequent. Eventually, Prof. Herrigel became frustrated, "gave up", and yielded entirely to the bow, with the result of obtaining mostly continuous achievement of the right quality.

At this stage, his master allowed him to progress to using an arrow - but the arrow would just flop down onto the ground after every release of the bow. This new stage of repetitive exercise was to continue for months, each time the arrow flopping to the ground not far from Herrigel's feet.

Eventually, the landing of the arrow in a far-distant target happened as a consequence of continued practice - the successful hitting of the target occurred as a side-effect, with the main exercise being the achievement of the right quality - that fusion of archer and bow in some state far removed from the mind that he initially brought to his practice.

This is Zen learning, and it fascinates me very much, permeating many of the Oriental arts, from archery, to flower-arranging, to martial arts... and, of course, to tea.

We brew tea day after day, month after month, year after year - water in, water out, water in, water out. This is practice, of a sort. Throughout this practice, something fascinating can be observed: we are learning tea, and its brewing.

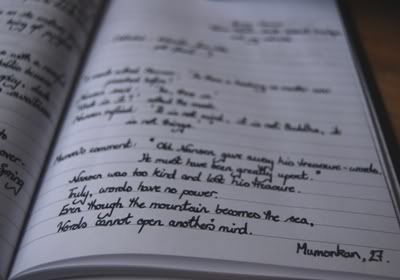

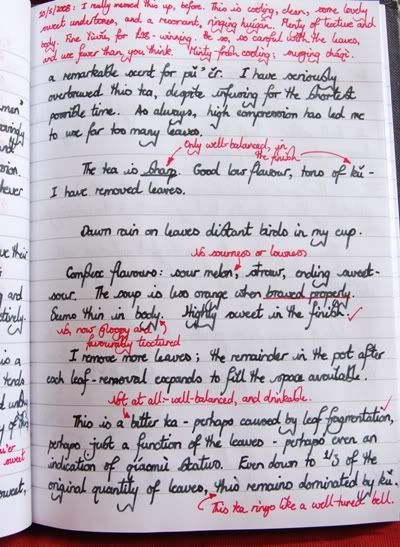

Up until quite recently, perhaps even as recently as a few months ago, I would count the passing seconds in my mind as the tea infused. I remember

writing about this about a year ago. It helped me lengthen the infusion times with each successive brew.

Just recently, my dear wife pointed out something to me that I had not noticed: I was no longer counting. I just poured water in, and then poured the water out. Though some infusions came out too strong and some came out too weak, the number of infusions with the right

quality were much higher than when I counted breaths. That is, the number of failures had drastically decreased - but they had decreased as a consequence of something having been learned, something that I could not adequately codify or communicate. The tea - just stopped being poorly infused (quite so often).

This is not a mystical process, and I am certain occurs in all our daily activities to some extent: the computer programs eventually stop having certain bugs in them; the paint eventually goes onto the canvas in just the right way; the flower arrangements somehow look "right".

This is learning the outer form, then the inner form.

This got me thinking about taijiquan.

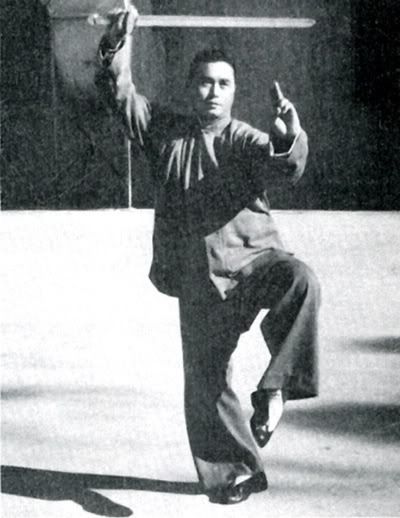

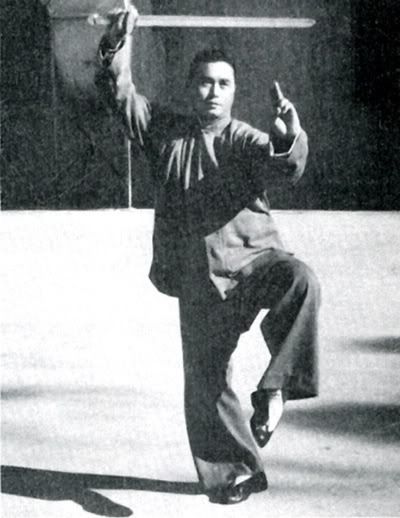

In taijiquan [tai ch'i, the meditative/martial form that one sees being practised in parks at dawn], the beginner initially learns the "outer" form. He learns a sequence of stances, and movements to get from one stance to the next. He learns where to put his weight, where to put his hands, where to fold his hip.

Once the outer form is learned, and the outer shape of the sequence of moves becomes unconsciously remembered, he can work on the "inner" form. He can learn where to put his mind, where to place the focus of his attention, where to move the more subtle parts of what the Chinese believe constitutes our physiology.

Progress in learning the inner form is immediately obvious in a certain quality of the outer form. That is, the outer form takes on that quality as a consequence of learning the inner form.

(Many video clips of famous taijiquan masters (and other "inner arts" such as bagua) can be found through the magic of YouTube - even clips of Master Zheng Manqing [Chen Man Ch'ing], who was personal physician to Jiang Jieshi [Chiang Kai Shek], and who is ultimately responsible for taijiquan in the West, can be found in grainy, ancient black-and-white video. To watch the outer form of such masters is to witness that quality which is a manifestation of their mastery over the inner form.)

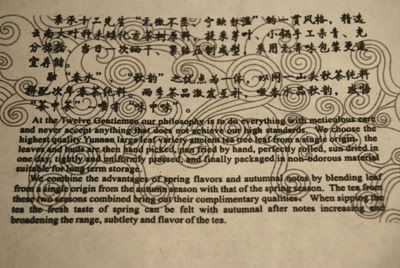

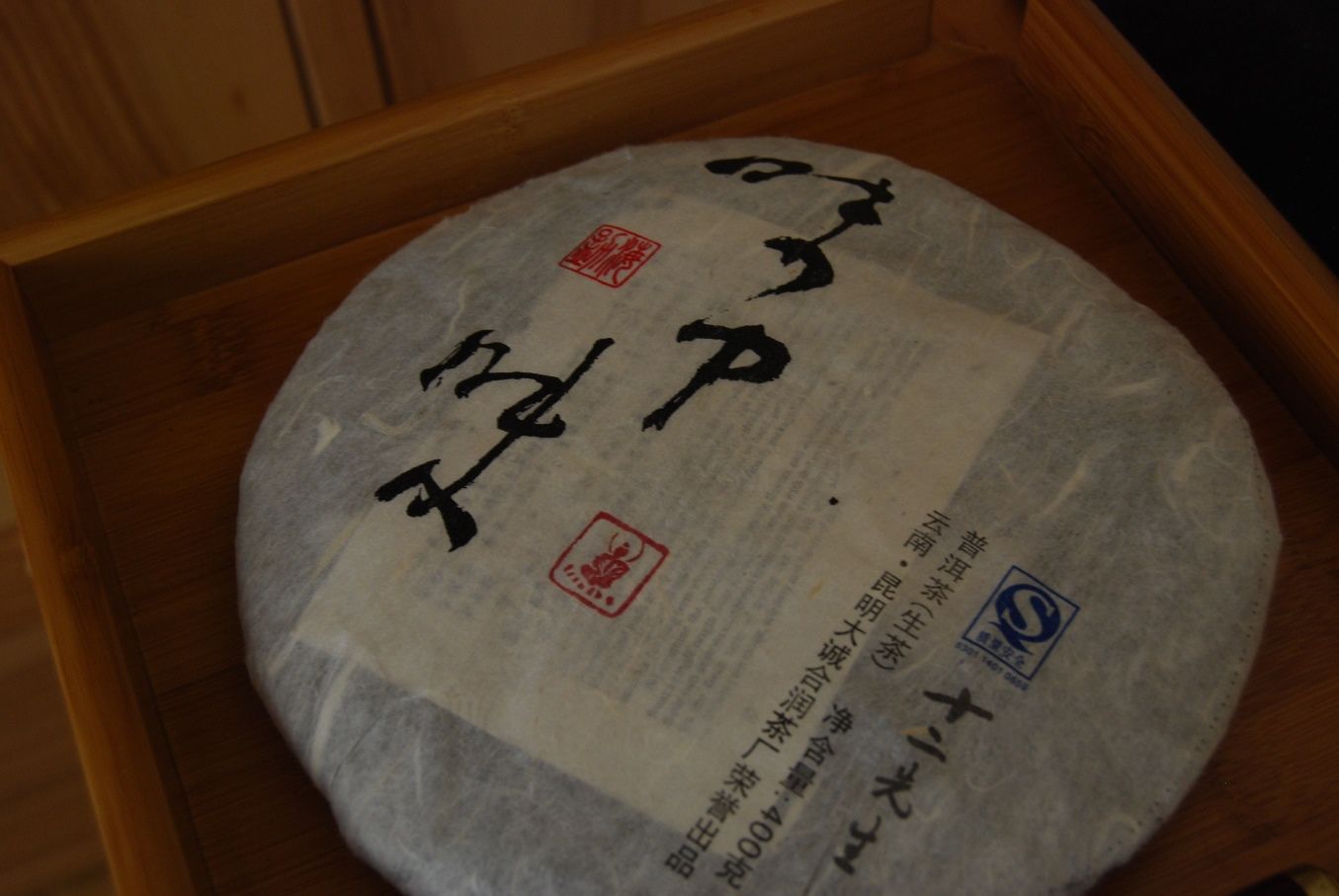

In tea, we learn the outer form first. I painstakingly learned the recommended "right" infusion lengths, the "right" vessels for each tea, the "right" amount of leaves to use, all from the words of others, just as if I was learning taijiquan again.

Then, we learn the inner form: brewing tight teas vs. loose teas, brewing dark green leaves vs. rusty orange leaves, brewing heavily aromatic pu'er vs. quietly-scented pu'er. We come to realise that there are no "right" parameters, only suggested outer forms, and we reorganise our own brewing according to our internal experience.

We brew, brew, brew, day after day, month after month. Eventually, something clicks, and the tea tastes good on occasion - the quality is good. Maybe this quality comes more often with time, and our intuitive feeling of what any particular tea needs becomes unconsciously more accurate. Eventually, the trappings of the outer form fall away as we no longer require them: the scales to weigh leaves, the timers to time infusions, the thermometers to measure water temperature, even (in my case) the counting of the passing seconds.

I'm no master, but it remains fascinating to see progression even in my humble and clumsy approach to tea. It's worth keeping an eye on.