I should preface this entry, which will be the usual transcription process from my diary, with a brief introduction. It will deal with the

Yi Jing (also known as the "I

Ching"), and may provide a little background for those to whom this is an unfamiliar subject. If any find themselves in such a position, I very much pray that this introduction fuels your interest, rather than dissuading you from further investigation.

Among its many functions, of which I shall not attempt to describe today, the

Yi Jing is an oracle. One may question it, through a well-defined method that has survived for many thousands of years (literally), and receive an answer.

So, then, we find ourselves to be on grounds which may be reasonably described as "superstitious".

Though I have studied science my whole life, I do not believe in science. Rather, I do not believe in an outlook to life which is limited by science, for I believe that it is the very nature of science to be limited.

By necessity, science is an abstraction of reality. Indeed:

there are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

I encourage healthy skepticism in all things. Buddha himself tells us not to accept anything that we cannot verify through personal experience. To the skeptic of the

Yi Jing, I would counsel: suspend your disbelief, if only for a while.

To that same skeptic, I would also hold up my personal experience of consulting the

Yi Jing in its capacity as an oracle. I have consulted this book on scores of

occasions throughout the past fifteen years that I have spent with it, and

every time have been left sincerely taken aback by the appropriateness of its answer. Each and every time it answers, it does so with the voice of a wise sage who has an intimate knowledge of the very specific problem that I have posed.

The famous psychologist, C.G. Jung, well-known for his theories of the collective unconsciousness, penned an insightful introduction to the first, and perhaps the most famous, Western translation of the

Yi Jing. He stated that, writing from his position of advanced age, he felt he could be honest in stating his respect for the

Yi Jing, without fear of scientific recrimination. He laid out what surely is the definitive argument in support of the

Yi Jing as an oracle, and in the footsteps of such an academic giant I shall not, cannot, follow. I point the reader interested in further reading to the standard work:

"I

Ching: The Book of Changes", by Richard Wilhelm, translated by Cary F.

Baynes. (1950)

The convergence of Western science with Eastern philosophy fascinates me without end. Zen teaches us that all of life is apprehended in this current moment; in fact, that all of life

is this current moment. As Jung argues, by consulting the

Yi Jing we are exploring that current moment - the current moment, because it contains all things, contains the seeds to its own solution. The

Yi Jing, he maintains, allows one to explore oneself. As

Gibran writes, we already contain the solutions that we seek:

Your hearts know in silence the secrets of the days and the nights.

But your ears thirst for the sound of your heart's knowledge.

You would know in words that which you have always known in thought.

Kahlil Gibran

The Prophet

Thus, the

Yi Jing may show us those truths that already reside within us, by virtue of the fact that all of life is contained within each of us: it is the proverbial string of pearls, each pearl of which is the string of pearls itself.

And so, today's

Yi Jing consultation. While quite a private practice, I hope that this article might prove interesting in being shared. The tea community is fortunate enough to lay claim to several

Yi Jing scholars, to whom I hope that this entry will not appear too clumsy. I won't do them disservice of naming them here.

Consultation of the

Yi Jing typically requires the phrasing of the question in such a way as to allow the book to "speak" properly. It does not provide yes/no answers, but offers cautions and predictions which are usually specific and precise enough to the phrased question to be uncannily useful.

It is very definitely

not the Magic 8-Ball.

---

Question:

"The Half-Dipper: what of its immediate future, and what cautions should be taken?"

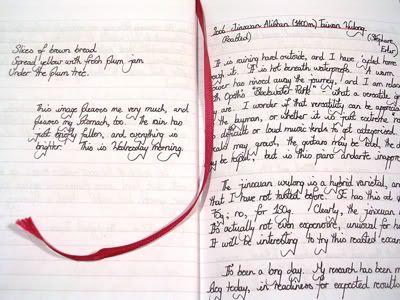

I use the

Wilhem (1950) version of the

Yi Jing, and now the Huang (1998) version as recommended by a fellow tea-drinker. The former provides a translation familiar to Western ears, whilst the latter is almost the perfect complement, being an excellent work by a foremost Eastern professor.

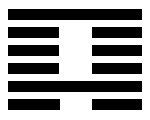

To answer the question posed, we construct a hexagram ("

gua") - a picture comprised of six lines, each line being "yin" or "yang". There are many methods of creating such lines, but the most traditional (and I believe most effective) is that of manipulating 49 yarrow sticks.

We are fortunate enough to use those shown above, made by my father-in-law for the purpose. It takes approximately 10-15 minutes to create a hexagram using a series of numerical manipulations that I won't detail here. The more modern methods of generating a hexagram that do not use yarrow stalks take less time, but I believe that the time taken is an essential part of the process. It is the meditation that allows one to understand the answer - to hurry is against the spirit of the exercise, much the same as it would be to hurry through

gongfucha.

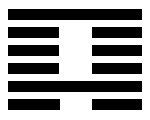

Effectively, the process is a large random-number generator, the outcome of which is six-line hexagram. In answer to my question regarding the Half-Dipper, I obtained the following, comprised of six broken (yin) and unbroken (yang) horizontal lines:

This hexagram represents the

current state of the situation. It describes what is happening

now, in relation to the question. Taoists believe that the world is in constant flux, and that change is the only truth. Each moment is an

everchanging interplay of yin and yang, positive and negative, active and passive. The created hexagram is a product of the moment, and thus it is believed to be a "snapshot" of the current moment, characterising the moment's essence.

We will see later how this hexagram that we have generated changes into another hexagram which indicates the

next state of the situation.

For now, let us see what the

Yi Jing has to say about the

current state, as given by the above hexagram. The book provides a number of texts for each

hexagram - each of the possible 64 hexagrams has its own character.

Thus, each moment is characterised by one of 64 prototypes. The genius of the book is that, somehow, the hexagram that is provided is specifically relevant to the problem.

One would imagine that, of the 64 situations, some will be inappropriate for a given situation. It is my experience that, not only are the hexagrams never inappropriate, they are usually uncannily accurate. It is the sort of observation that one can only state with confidence, without fear of the recrimination that Jung noted, after trying it out for oneself. Accept nothing that cannot be personally verified...

The text of the book is large, and layered like an onion. Each layer is attributed to various historical sages. The

coremost text is provided by King Wen; surrounding that text is a layer attributed to

Confucious (who famously stated "if I could have another lifetime, I would devote it to further study of the

Yi Jing").

Current state:

Hexagram 12 - Meng ("Childhood")

After birth, there is childhood. This hexagram, "

Meng", at the time of the authors' writing, referred to the wisdom inherent in childhood that is waiting to be uncovered. It is the innocence of youth (what one source terms the folly of youth), from which wisdom can be coaxed through education and enlightenment.

The themes of the hexagram are auspicious: the beginning of a life, the potential uncovering of wisdom.

In generating the hexagram, some lines are assigned particular emphasis (in fact, indicating that they are about to change from yin to yang, or from yang to yin). In drawing

Meng, I obtained such emphasis on three of the six lines, for which further text is provided:

The first emphasised line symbolises the magnanimity of the teacher, in his providing something in the way of education. His magnanimity brings about good fortune. The teacher is ready to teach.

The second emphasised line gives a note of caution: humiliation can occur if one loses touch with reality; isolation is a danger to be avoided.

The third emphasised line indicates that the education is well-received. This also brings about good fortune. The student is ready to receive the teaching.

Before we interpret these statements, let us first turn our attention to the

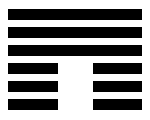

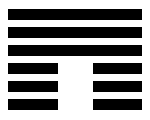

next state. In fact, this is derived by changing the three emphasised lines (those mentioned above) into their opposites: yin into yang, yang into yin. The next state that I obtained is:

Here we have taken the current state,

Meng, and inverted lines 2, 4, and 5 (where the bottom line is 1, counting upwards to the top line, 6), in accordance with the original generation via the yarrow stalks.

Next state:

Hexagram 12 - Pi (Hindrance)

This hexagram represents a warning that stagnation may occur after the previous pleasant situation. A caution is given to avoid such stagnation: one must not seek, or become attached to, success. One must not strive for high position nor handsome payment, but remain true to himself. In doing so, by showing his integrity to his cause, potential calamity can be avoided.

---

Thus, we have seen the current state, and the next state, relating to our question.

The current situation is a very positive one. It is uncanny in that it has identified that a birth has recently occurred. It indicates that there is potential value waiting to be revealed. I cannot lay claim to Half-Dipper being a good educational resource, but if it provides useful to others, as well as being an electronic repository of my own notes, it will have served its purpose. This theme is provided by the text: the educator is willing, the student is willing - good fortune.

It cautions that it must stay in touch with reality, specifically stating that to isolate oneself, to retreat into oneself, would bring misfortune. I have long held that some blogs are the ultimate in vanity publishing - I believe informative blogs, such as tea notes, are exempt from this criticism, providing a useful function. I very much hope that Half-Dipper can serve a function other than the pontification of the Self. A wise caution from the

Yi Jing, indeed.

The coming situation is a strongly-worded caution: one must not chase rewards or position, but remain true to original purpose. This is wisely said. Already, I have faced the temptation of being kinder to a tea in my transcription from my diary, softening my words, because I know that the vendor might be reading. In such cases, I have held true to my original notes, and aim to continue to do so. How wise is it for an endeavour to remain true to its purpose without striving for the vulgarity of reward?

Critics of the

Yi Jing have made the ill-informed comment that any hexagram can be interpreted to fit any situation, and thus it always appears to be giving good advice. I cannot concur, as a simple reading of the various hexagram shows their unique and individual characteristics. The power of the book, or the power of what it reveals working inside the human psyche through the lens of its accumulated wisdom, is that good, specific advice is (in my experience) invariably provided.

One of the small joys of my life are those rare

occasions on which I am fortunate enough to read the

Yi Jing for someone else. For those still suspending their disbelief, thanks for bearing with me.

Postscript: After writing, I notice that

VL has produced an interesting piece at

Tea Logic, musing on the concept of change, while I have been working on this article. It just goes to show that there is no such thing as coincidence... As Jung himself would say, just more evidence for the synchronicity of life.

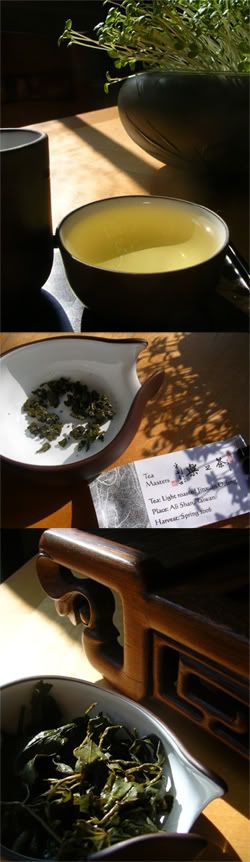

Leaves:

Leaves: