So, we meet at last, Other Teas from

Tea Urchin.

Today's article collates a set of teas kindly provided by Eugene, the Strahlian force behind the Tea Urchin shop, whom I suspect may have more than a little Chinese DNA in his own ancestry. If you've not yet checked out his shop, I urge you to do so, for the aesthetic appeal as well as the tea. Given the appearance of most on-line tea businesses, Tea Urchin stands out. The first bite is taken with the eye, after all.

The cakes pictured above and below (the Guafengzhai and Luoshuidong) are both samples covered by this article. I've been impressed with those cakes that I have described so far (the

Charen Bangwei, and

a pair from Gaofachang). However, I alluded to the fact that some other cakes have impressed me less; I cannot dissemble - "honesty is the best policy". So, here we go. If you're the owner of Tea Urchin, you may wish to stop reading now.

All four of these cakes struck me by being obviously red when dry. Alarm bells rung the very moment that I examined these; my notes for each express sentiments on the same theme: "Uh-oh, red leaves." Perhaps these are, in contradiction to my previous experience, red leaves on an unaged cake that are somehow powerful and potent. Perhaps. Let's find out.

It may not be obvious in the images below, due to the eternal battle between me and my camera's colour balancing functions, but it's unarguable when seen under daylight. The aroma (when dry) of each tends to be quiet and muted, in accordance with my prior assumptions for red leaves. Uh-oh.

Luoshuidong

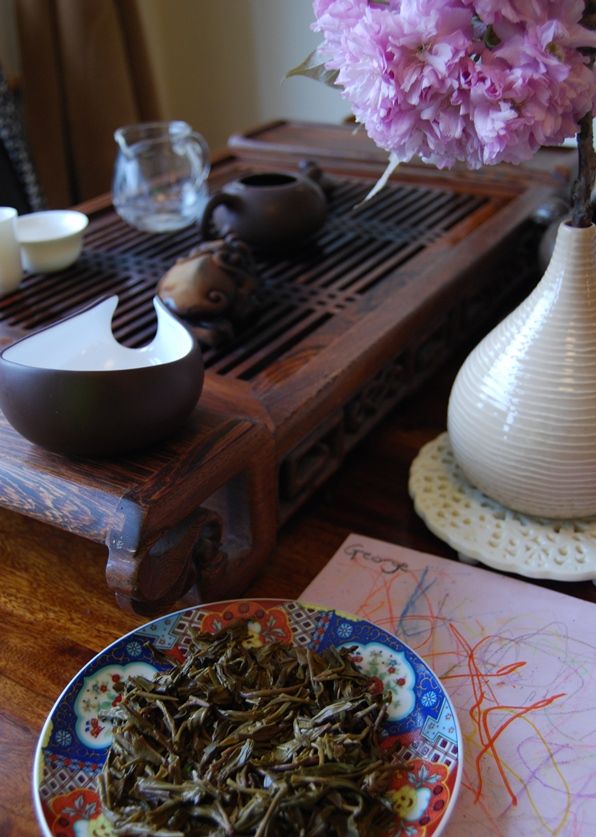

However, before we dive into the characteristics from the soup, we must pause to make mention that all of these leaves, apart from their colour, are very pretty to gaze upon. The leaves are well-handled, they have a decent shine, and retain much of their original fur. The appearance of the leaves suggests that Eugene knows how to select good leaves.

Guafengzhai

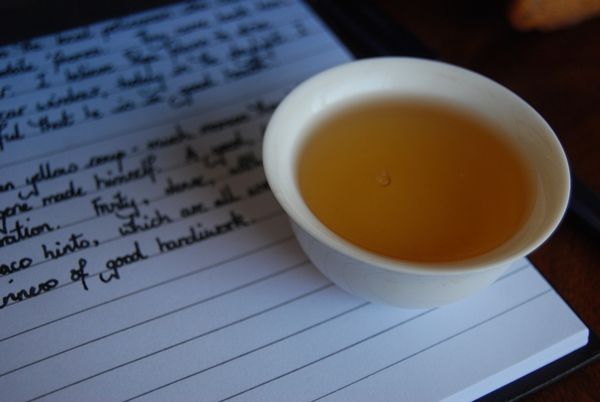

Alas, the pinmingbei [tasting cup] tells the same story in each case, for the Guafengzhai, Luoshuidong, and Dingjiazhai. (I will come to the Laoman'e later, which is a different story.) Each of the three former cakes are from the same region, being Yiwu-area cakes, and are all autumnal.

Guafengzhai

I found each of the autumnal trio to exhibit the same character: the orange soup is constrained, limited, unexalted, unenduring in the throat, and tends towards the flavour of "hongcha". In every case, the quality of the leaves is clear: trying to make themselves heard from under the smothering blanket of hongcha that has robbed them of their charm, the leaves exude a cooling sensation, and have some vibrancy on the lips and tongue.

Luoshuidong

Each of these three orange autumnal teas disappointed me, because such limited teas have a very "low ceiling", that prevents me from enjoying them to a great degree. I put this to Eugene, feeling rather terrible for doing so. After all, this is a man's livelihood with which I am taking issue, and I wish for nothing but success for what seems to be such a labour of love.

Eugene took it all in his stride, and noted that the autumnal leaves tend to be much heavier in terms of water content that the premium spring leaves. This leads, he tells me, to his producers erring on the side of caution when it comes to the wok - they keep the leaves in the heat for as long as they dare, to remove as much water as possible, but they cannot push too hard lest they burn the leaves.

The result is that shaqing is not completely performed, and the leaves therefore continue their oxidation - much as hongcha, hence the characteristic that I had encountered.

Dingjiazhai

He noted that Gaofachang cakes managed to mitigate this effect to some degree by careful removal of red leaves from the blend after processing had been completed, which accounts for the substantially higher prices of the Gaofachang cakes compared with the Charen cakes. My notes have: Guafengzhai ($97/357g), Dingjiazhai ($65/357g), Luoshuidong ($43/357g) compared with the Gaofachang spring Mangzhi ($102/357g) and Gaofachang autumn Yibang ($85/357g).

The result, then, is a very large quantity of tea that is "capped", rather limited, and which has strong hongcha overtones. The colour of the Guafengzhai leaves below speaks volumes, for example.

Guafengzhai

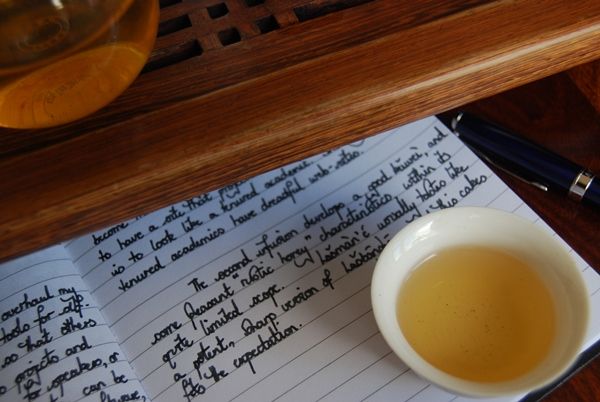

I mentioned above that the Laoman'e cake was different, and indeed it is: the leaves are from summer, not autumn, and the price is a reasonable $41/357g. While there are a few red leaves, they are in the great minority, when compared with the majority of proper green leaves.

This soup is different, in that it has a green-brown shade; the second infusion develops a kuwei [good bitterness] far in advance of the trio of autumnal cakes, and has some "rustic honey" within its fairly limited scope. The body develops floral scents, and it dwells nicely in the throat. I wrote that "it is absent its heart", in that it seems empty in the centre of its body. However, it is a great step up from the previous teas, and I stick around at the tea-table for a long time to see how it develops.

Laoman'e

Making autumnal cakes seems fraught with difficulties, and I am not entirely clear why people continue to push ahead with making them. Eugene can pick excellent leaves, as evinced by the good underlying characteristics of the maocha in each of his productions, but the results for autumnal leaves are not excellent to my mind.

Who am I, a laowai, to say how a man should run his business? I share with you only my opinions, such as they are, for you to compare with your own conclusions. It is my hope and expectation that Tea Urchin will join the ranks of my favourite suppliers in the coming years, to give us more of those cakes that the excellent spring Bangwei demonstrate are possible. I understand that, since writing this article, some 2012 cakes have become available, which, most importantly, are spring cakes.

Running a tea business much be exceedingly difficult.

Edit: I accidentally published this article earlier, rather than queuing it for eventual publication today; in the short while that it was available, a comment was made which I reproduce here to avoid losing it:

Dear Hobbes, I would like to point out that Yiwu is probably the toughest area to source tea. In the Yao area, on the eastern part of the mountain range, there are widespread problems with the manufacture. It is actually very hard to find a perfectly processed Gua Feng Zhai or Ding Jia Zhai tea. I have made it four times to those villages and I haven't managed to find decent mao cha yet, the tea has a very good Chaqi, but I always find something wrong in the taste. I hope it will get better in the future! All the best! William