This is the first of the five Xizihao samples from Sanhetang, produced by Guoyan Factory. For previous purple-faced, vein-throbbing vitriol regarding the correct pinyin spelling of this tea, see here.

Market diversification is working its course with this premium range of teas, which is now being sold by Yunnan Sourcing (and also, though not yet on sale, presumably to arrive soon at Houde).

Five cakes are on offer: two premium expensive varieties, and three cheaper offerings - presumably capitalising on the "strength of the brand" while selling to the lower end of the market (the cynic in me thinks of "Calvin Klein" t-shirts).

The two expensive cakes are named "Yuanshilin" [virgin, untouched forest] and "Huangshanlin" [abandoned, desolate forest]. Again, the cynic in me wonders if these are merely poetic ways of saying "yesheng" [wild], the usual claim for upper-end pu'er. As with claims to being yesheng, the sensibily wary consumer treats virgin/desolate forest claims with an equal measure of caution.

This introduction serves, no doubt, to underline that in pu'er, much as in other largely unregulated ventures, the consumer has to be exceptionally careful. "A fool and his money are soon parted", runs the phrase, and modern brand-based approaches to marketing tea seem no different.

Caveat emptor...

The origin of today's cake (the aforementioned Yuanshilin) is, according to Yunnan Sourcing, Pasalaozhai. This could be Mengpashashan, which is used to make organic Haiwan Factory cakes, as they have similar-charactered names, and are both "South Menghai County". More information, as ever, is always welcomed.

Enough providence - is this expensive tea any good?

Brita-filtered water @ 100C in 12cl shengpu pot; ~6-8g leaf; 1 rinse

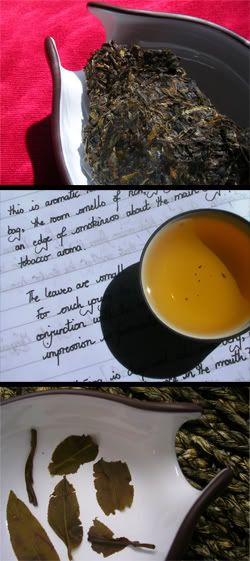

Dry leaf:

Dry leaf:This is aromatic tea. Even though sealed in a plastic bag, the room somehow smells of rich, young pu'er leaf. It has an edge of smokiness around the main, tobacco body though it is often noted that this smokiness lessens with age.

The leaves are small, suggesting a spring picking. For such young tea, it is surprisingly dark. Alarm bells commence their ringing, and I wonder if this has been processed (read: partly oxidised) in order to capture the attention of the immediate market.

3s, 3s, 4s, 7s, 15s, 25s, 40s, 60s:

Right from the very first infusion, this is a thick, dark-orange tea. Concerns about the processing abound.

The beidixiang is immense in its duration, truly. It is deep, and rich, and lasts several minutes, before eventually fading into a somehow even longer lengxiang of sweet-sugar. Will this endurance continue in the pinmingbei?

This tea has two characters.

The first is seen in the initial three infusions: it is thick, orange, and a "dark fruits" pu'er, indicative of the old favourite processing techniques for making a tea immediately appealing. See the central illustration (taken from the second infusion) for an illustration of its unusually dense orange colours at this initial stage. There is an up-front tartness felt right at the lips, which then gives way to a rich set of tobacco flavours, especially present in the yunxiang [lingering aroma after the swallow]. It has a decent, potent ku.

The second stage appears around the third or fourth infusion, where the tea abruptly changes character: the orange colour changes to pure, solid yellow; the "dark fruit" character changes to a mushroom sweetness.

By the sixth infusion, it is becoming simpler, though the ku continues onwards admirably.

Lei came in from her laboratory while I silently poured the eighth infusion, and sat down to a cup, saying, "Is this the eighth infusion?" I'm impressed!

Wet leaves:

Tiny and pretty, though mostly fragmented and inclusive of many leaf-free stems. It's quite messy - something I have heard attributed to the current trend in Taiwanese pu'er manufacturers.

Some leaves are darkened, and partially oxidised, as if they have had a nudge away from their (I would argue, preferable) green state by some interesting processing choices. Hence, the initial solid orange soup, and "dark fruit" character.

Overall:

It's clearly a good leaf: it has tons of power, and lasts a very long time. I have objections with the leaf fragmentation (I don't like the mulch-based approach to some modern pu'er manufacture), and I have objections with the processing (just give me a pure, unoxidised pu'er leaf for mercy's sake! It's not dancong!).

It is tasty, it is a quality tea, and, obviously, it is overpriced. Each of us weighs these points in conjunction with what we're prepared to spend in our tea. It does deliver a pleasant experience, but it does not deliver value for money. I would be happy to own perhaps 1 or 2 of these cakes for amusement's sake, but buying a tong is absolutely out of the question for me - it's simply unjustifiable, to my mind.

17 comments:

Looks nice...

So, in order to produce the oxidized effect in its first year, do you think this was oxidized before being pressed into a cake, or underwent partial wet storage ripening?

Well!

Given that this cake is no more than half a year old (presumably much less), interesting effects surely have to be caused by processing rather than storage. There's no dampness, just that tell-tale redness...

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

As unjustifiable as these prices are, there's yes, an even more exclusive XiZhiHao (and I like that spelling, so there, nah-na-nah), the XZH Din-Ji "Yan Shing" which is now available through Hou De. I will never buy a cake at that price, but I did order a sample just to see what the fuss is all about.

DC and I periodically (not always) have very different experiences of the same tea, and this, the XZH Yuan Shi Lin is one of them. While DC describes this tea as having "tons of power and lasts a very long time" I found it weak and dropping off by the 4th infusion, with notes of lucha grassiness, similar to what I was finding in the XZH 7542. Today I brewed the 8582 next to the Huang Shan Lin. The 8582 is the only one of the 5 that I am tempted to buy more of. (The Huang Shan Lin has a metallic component to its ku, a distinct iron taste that I noticed both the first time I brewed it, and also in today's comparison. I'm very curious to see whether or not you note a similar taste, DC.) I may save the rest of the 8582 sample to see what it tastes like next to the Din-Ji "Yan Shing" from Hou De.

Excuse my lack of manners. Congratulations on the house moving. Moving is considered right up there just after death and divorce as one of life's more stressful events. I'm sure you're glad to be done with it.

speakfreely -- how did you brew the tea?

The more expensive Hou De Dingji is indeed entering exorbitant category.

Dear Carla,

Many thanks for the comments. I notice with considerable amusement that, just as we've come across many times in the past, we're at odds over this one, once again!

I wonder if I've used more leaves than you, with this Yuanshilin. Like you, I noted a shift around the 3rd-4th infusion. However, for me, it took a step into a different character - for you, it seems to have just collapsed.

I used a 12cl pot which was quite heavily loaded with leaves. I should add that when I give an estimation of leaf weight in my brewing parameters, it is just that - an estimation. You know how I feel about measuring devices in a tea session! In this case, I wonder if it has brought out a little something further in the tea. As you can tell from my list of infusion times, this tea really did show some endurance for me.

I don't recall observing any metallic notes, but I wonder if I subsume them in my descriptions of dark fruitiness.

It is also worth noting that, courtesy of our house moving, I have been using Brita-filtered water for the last run of tea sessions. In comparative tastings with our usual water (the bottled "Caledonian Springs" from Sainsburys, a UK supermarket), the Brita water flattens the entire flavour profile, especially the high, floral notes and the more mineral aspects. I have found that brewing tea with Brita-filtered water to be like looking out of a slightly grubby window. Of course, this is a function of the basic water, which in our case is the rather chalky Oxford mains supply.

Thanks for the kind words with the move! We're working our way through the boxes each morning and evening. Amusingly, one of the first priorities was setting up the tea table so that we could drink properly. "Where's the chahe?" "I don't know, but I found the small gongdaobei!"

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

P.s. Following your comment, I went to check out the other Xizihao cake at Houde.

I must be honest (as you would expect little else from me, I hope): based on the price alone, it seems to be fairly silly. I struggle to envisage exactly what I would expect from a six-month-old tea to be worthy of that figure. Like you, I will try the sample and reserve judgement on the value of the cake until then.

I brewed the XZH Yuan Shi Lin in my 150cl sheng pot in the standard way that I start with a sheng I haven't tried before: 5s rinse, 30s (or more) wait, 5s 1st infusion. Even if the 1st infusion is a little weak, I usually restrain the 2nd to 5-7 seconds, as it will generally come out stronger as the leaves get a chance to open. If it's still weak, I extend infusion times. Like DC, I don't actually measure the leaf, but knowing these were 25g samples, I was trying to use 1/3 of the sample, or about 8g.

So, looking back at my notes, I realize I should be more specific about the weakness I was experiencing in the Yuan Shi Lin. It wasn't actually any lack of ku, but rather the soon-watery character of the supporting flavors. I never detected any of the "dark fruit" flavors that DC did, rather the tea presented as vegetal, sweet wood-sap with a bit of longjing "bean" in the background. The bitter predominated, but stayed in my mouth and did not move down the throat to produce hui gan. The additional flavors began to fail and become watery in the 4th infusion.

Interesting - thanks as ever, Carla. I tend to do something similar with the infusions, but they start at 3s given my slightly larger leaf:water ratio.

You know, I do remember thinking "this is a bit loose" to myself, which is my mental short-hand for a touch watery in the middle. It surely cannot be coincidence that your observed failure in flavour occurs around the same time as I noticed a change into is second phase.

I'll be sure to keep a critical eye on it for the subsequent brew - thanks again for your detailed notes.

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Greetings Hobbes,

I don't think I made myself understood with my last question. I was just wondering if you suspect the oxidized character to be due to pu-erh shu ripening, or is it possible that it was oxidized before being heat-treated? Is the second option out of the question? As I understand, all pu-erhs are heat-treated ("kill-green" to stop oxidation) at the completely unoxidized or green state, and then post-fermentation can occur by either wet or dry storage, producing a shu or sheng pu-erh respectively. There's a lot of contradicting information out there.. we would sure appreciate the opinion of a knowledgeable authority on this.

Oodletip:)

perpleXd

Dear Perplexd,

Many thanks for the further comment. I'd definitely not claim to be an authority, just a soul that drinks far too much tea!

The shupu ripening, as you rightly say, is a latter-stage oxidation, and it certainly didn't used to be too unusual to get "shengpu" bing that had been partly ripened in this way (which is often termed "partly cooked" of course). However, it's usually fairly easy to spot this, as it has a tell-tale shupu character.

More often, one comes across bingcha that has been made more palatable for immediate consumption through the prior steps of processing. Truly green shengpu is an energetic creature, and often has a ton of ku (straight bitterness throughout the mouth). Some processing steps can be taken to reduce this, and to partially add some more fruity characteristics. As one correspondent so correctly wrote, it is the "wulong-isation" of pu'er, which is what I refer to as making it look like a dancong: the edges of the leaves are oxidised (perhaps intentionally) in order to produce a fruitiness. The can bruise the edges of the leaves to cause the juices to be exposed to the oxygen in the air, which result in the tell-tale red oxidation around the edges. The longer the tea is left in this state, the more is oxidised - usually continuing until the shaqing [kill-green] stage is performed, to halt further oxidation.

A further step that can be taken in the drink-it-now bing is to simply allow the leaf to oxidise over time due to the decomposition of the chlorophyll in the leaves (which the Chinese, possibly erroneously, term "fermentation"). This would turn the leaf into hongcha is left to complete. There are several bing that you'll encounter that taste of dianhong to a greater or lesser degree, which can indicate this process - sometimes just an inadequate shaqing stage, resulting in further undesired fermentation. One example is the 2000 Jingmai "Ruyi" that I described before.

In all honesty, I suspect it is good Xizihao business practice to make their teas appear more immediately appealing, so that they can sell more. I regard this as potentially selling away the tea's future, though, as it is a short-cut to the ultimate beauty of slow time-aging that can make shengpu so great. This is perhaps why I prefer the Huangshanlin and 8582 of this batch, as they are the closest to being "true" shengpu in my opinion.

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Thank you for the astute explanation! I am still unable to find an obvious translation in my dictionary for many of the Chinese terms you use. This is mostly because I can't narrow it down to one of the four tones of standard Pinyin without your inclusion of the markings. It would be even cooler if I could just mouseover each word and see the chinese character and translations. I don't know about the rest of your readers, but my interest in tea definitely crosses over with my interest in Chinese culture... and as with any culture, language is key. Have you considered using standard pinyin in your blog?

Dear Perplexd,

Indeed I have, it was one of my first concerns in setting up the Half-Dipper, in fact. I spent some time trying to find a suitable way to input pinyin with the four tones, but could find no reasonable method of doing so (short of cutting and pasting the individual characters as required from a Unicode listing). Do you have any thoughts on how I could do so? The various IMEs supplied with Windows just seem to provide ideograms rather than pinyin.

Until then, just for translating the tea terms (which I try to define in square brackets if they're a bit unusual, such as yunxiang), I heartily recommend Mr. Perin's excellent Babelcarp web-site.

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Well, this website is great: http://www.chinese-tools.com/tools/pinyin-editor.html

Also, if you don't mind the aesthetics of it, you could put the number of the tone after each word, i.e. gong1 fu1 cha2.

Although the first is probably preferable :) It looks neat, and might intrigue the unfamiliar to learn more about Chinese.

Peace,

perp'd

Great stuff, thanks for the recommendation. I'd only use pinyin proper, I think, writing pin1yin1 gets really hard to read!

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Sanhetang currently (and I don't quite trust it, but it makes sense based on leaf size and flavor profile) sez that Yuanshilin is Manzhuan from Manlin village. Given that at various times, Hekai and Pasha have also been claimed, best to be cautious as to what it actually is.

Dear Shah,

Thank for the update, and well done on your archaeological excavation of my ancient articles. :)

Gosh, these older articles do look dreadful.

Toodlepip,

Hobbes

Post a Comment