Part II of his essential guide,

in which Hobbes tells you how to raise a cup to your lips,

put tea into your mouth, then swallow.

in which Hobbes tells you how to raise a cup to your lips,

put tea into your mouth, then swallow.

It's nearly summer, it's beautiful outdoors, and you're stuck in front of your computer reading about tea. Are you ready to admit that you're a tiny bit sad, yet?

Yes, you're one of us. Come play with us, forever, and ever, and ever...

(For disclaimers about how this reflects personal experimentation, and should be immediately disregarded, see the previous article.)

Here are some more notes on how I sometimes look at tea. Don't get caught up in process or routine - read this, then forget it. Drinking tea would be a huge chore if you followed the same mechanical procedure each time, unless you really enjoyed it. The following is more of a vocabulary from which individual observations might be drawn (if you're me). Your mission, as a tea drinker, is to find a vocabulary that works for you. Don't get bogged down in other people's vocabularies unless it's working for you. Be honest with yourself, and keep only what helps. There is no real map for enjoying tea.

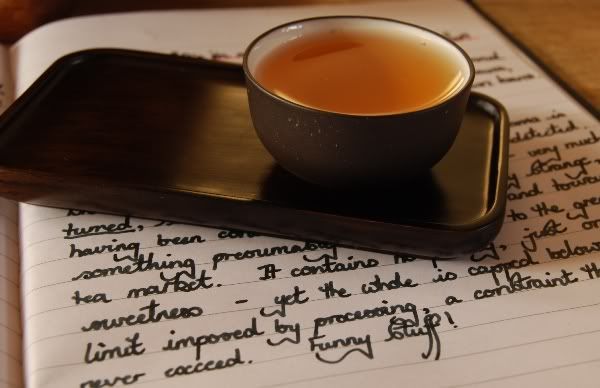

Having successfully negotiated the process of getting tea into the mouth, I notice what happens from lips to throat.

Here are some more notes on how I sometimes look at tea. Don't get caught up in process or routine - read this, then forget it. Drinking tea would be a huge chore if you followed the same mechanical procedure each time, unless you really enjoyed it. The following is more of a vocabulary from which individual observations might be drawn (if you're me). Your mission, as a tea drinker, is to find a vocabulary that works for you. Don't get bogged down in other people's vocabularies unless it's working for you. Be honest with yourself, and keep only what helps. There is no real map for enjoying tea.

Having successfully negotiated the process of getting tea into the mouth, I notice what happens from lips to throat.

What about my lips and throat?

The first impression comes as early as the first contact of soup on flesh.

Good tea can be energetic. That is, it can impart a certain liveliness, an almost effervescent quality on the lips that... tingles a bit. It can also be felt where it first touches the tongue. It is a tangible sensation that suggests energy, life, and Good Stuff. In my humble experience, this correlates interestingly with non-plantation leaves, though I have had a small number of plantation teas that also show the same effect. It's a good sign, I think, like a lively grape.

With the tea now in contact with your mouth, the product of aeons of evolution kick in and the volatile organic compounds slopping around in the tea-water get involved with your facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves, with your piriform cortex, and ultimately, your orbitofrontal cortex. That is, you taste it and smell it, then decide if you like it.

Good tea can be energetic. That is, it can impart a certain liveliness, an almost effervescent quality on the lips that... tingles a bit. It can also be felt where it first touches the tongue. It is a tangible sensation that suggests energy, life, and Good Stuff. In my humble experience, this correlates interestingly with non-plantation leaves, though I have had a small number of plantation teas that also show the same effect. It's a good sign, I think, like a lively grape.

With the tea now in contact with your mouth, the product of aeons of evolution kick in and the volatile organic compounds slopping around in the tea-water get involved with your facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves, with your piriform cortex, and ultimately, your orbitofrontal cortex. That is, you taste it and smell it, then decide if you like it.

My orbitofrontal cortex happens to like cow parsley.

Just like the aroma cup, you get hit by the "light" volatile compounds first - you sense the higher notes of sweetness, floralness, and so on. If it's Yiwu, Banzhang or Mengsong tea, you might be getting plenty of sweetness at the outset.

Then, the "heavier" compounds make themselves felt, and you get some bass components. You might get undertones of leather or grain. If it's a Lincang tea, maybe there's some sort of cereal-crop effect at work.

You'll also be getting plenty of information (the majority, in fact) from your nose, as the compounds head upstairs from your mouth. I make plenty of use of this stage, as I love those tobacco-like effects that dwell back there. I'm a vicarious smoker, and this is my substitute. Ahhhhh...

Then, the "heavier" compounds make themselves felt, and you get some bass components. You might get undertones of leather or grain. If it's a Lincang tea, maybe there's some sort of cereal-crop effect at work.

You'll also be getting plenty of information (the majority, in fact) from your nose, as the compounds head upstairs from your mouth. I make plenty of use of this stage, as I love those tobacco-like effects that dwell back there. I'm a vicarious smoker, and this is my substitute. Ahhhhh...

And bark. Some teas definitely have barky notes.

So, you've been witnessing that progression from high-notes to low-notes, as it swells in the mouth. You've been getting plenty of nose into the bargain. What about the texture? What does it feel like in the mouth? Is it a chunky, gloopy, viscous monster, stuffed full of beefy contents? Or is it a thin, weedy affair, that feels like it's been stretched too thinly? Some really heavy teas almost feel as if they're adhering to the roof and walls of the mouth. Some watery, worn-out leaves pass like water.

If you hadn't guessed by now, one of my objectives is to find tea with contents. I like bold, chunky teas with plenty of stuff in them. Overstretched soil and high yields can, unsurprisingly, lead to empty teas. Any guesses what might happen to those after twenty years? I'd hazard a guess that the teas with content are going to fair better with time, and that intuition (which had bloody well better be right) guides my tastebuds. And, to a large extent, my wallet. I don't have time for teas which are waifs, ready to disappear in a strong wind. I have too many old teas that have simply become empty - mostly old maocha seems to suffer from this.

If you hadn't guessed by now, one of my objectives is to find tea with contents. I like bold, chunky teas with plenty of stuff in them. Overstretched soil and high yields can, unsurprisingly, lead to empty teas. Any guesses what might happen to those after twenty years? I'd hazard a guess that the teas with content are going to fair better with time, and that intuition (which had bloody well better be right) guides my tastebuds. And, to a large extent, my wallet. I don't have time for teas which are waifs, ready to disappear in a strong wind. I have too many old teas that have simply become empty - mostly old maocha seems to suffer from this.

Some older examples can seem tired out.

With flavours and aroma progressing nicely, we might be getting to the throat. Acidity at the end? Bitterness? What's happening back there? I like some acidity - a little bit of challenge. I quaff Bulang by the bucketload in a quest to find my perfect acidity. My body appears to like it.

(Important note: your physiology is your own, and you're going to have different reactions to different teas. Chinese medicine would prescribe "cold" drinks like, for example, brutal green Bulang for "hot" conditions, and would prescribe "hot" substances like, for example, roasted teas and hongcha, for "cold" conditions. Most orientals I know have generally "cold" complexions, and can't tolerate much coldness; most Westerners have "hot" complexions and seem to thrive on it. Whatever the details, and whichever system of physiological analysis you subscribe to, be careful with what you drink. Moderation in all things is the key, and sensitivity to your own conditions. Keep an eye on yourself, and let your body guide what you drink.)

(Important note: your physiology is your own, and you're going to have different reactions to different teas. Chinese medicine would prescribe "cold" drinks like, for example, brutal green Bulang for "hot" conditions, and would prescribe "hot" substances like, for example, roasted teas and hongcha, for "cold" conditions. Most orientals I know have generally "cold" complexions, and can't tolerate much coldness; most Westerners have "hot" complexions and seem to thrive on it. Whatever the details, and whichever system of physiological analysis you subscribe to, be careful with what you drink. Moderation in all things is the key, and sensitivity to your own conditions. Keep an eye on yourself, and let your body guide what you drink.)

I prefer medicinal philosophies that prescribe muffins for most ailments.

Back to the acidity/bitterness, and other throaty goodness. Plantation teas can feel "rough" at this stage - they could get abrasive around the throat, and that's never a good thing. Good tea never hurts, or feels uncomfortable. If it has bitterness, it has a good bitterness, that you enjoy, and that challenges, but doesn't abrade. Bad tea, on the other hand, can be as rough as a German woman's legs*. Rough, rough, rough. That's no fun for anyone.

*Ich mag die Deutsche Frauleinen, btw. Sie sind sehr schone und Teuflisch!

Some wine folk like to "chew" the wine, and I've seen teafolk ape this. The idea is to get some air into the mixture, and to spread the fluid over the mouth - disturb it, and provoke airation into the nose. Amusingly enough, I've seen plenty of old Chinese chaps do the same with their pu'er, in which they take a little right at the front of their mouth, on their tongues, and then draw air in through the tea, making a slurping, pftttfffth'ing noise. If this works for you, brilliant. I don't find this so enlightening, but it's another technique in the bag for you to try.

My personal favourite is to hurrrr a little air, slowly, into the mouth from the lungs, at the same time as flexing the tongue to guide some of the brew towards the nasal cavity. I keep the nose open and smell the vapours very gently. This works for me, and helps me to check out the content via scent, amplifying some of the contents. If this sounds like voodoo, disregard it. Wine chums have called this "reverse smelling". Bless 'em. Basically, it comes down to working your sensing equipment in such a way that you can get what you want from the tea. I've no idea how your equipment works, but urge you to find out.

*Ich mag die Deutsche Frauleinen, btw. Sie sind sehr schone und Teuflisch!

Some wine folk like to "chew" the wine, and I've seen teafolk ape this. The idea is to get some air into the mixture, and to spread the fluid over the mouth - disturb it, and provoke airation into the nose. Amusingly enough, I've seen plenty of old Chinese chaps do the same with their pu'er, in which they take a little right at the front of their mouth, on their tongues, and then draw air in through the tea, making a slurping, pftttfffth'ing noise. If this works for you, brilliant. I don't find this so enlightening, but it's another technique in the bag for you to try.

My personal favourite is to hurrrr a little air, slowly, into the mouth from the lungs, at the same time as flexing the tongue to guide some of the brew towards the nasal cavity. I keep the nose open and smell the vapours very gently. This works for me, and helps me to check out the content via scent, amplifying some of the contents. If this sounds like voodoo, disregard it. Wine chums have called this "reverse smelling". Bless 'em. Basically, it comes down to working your sensing equipment in such a way that you can get what you want from the tea. I've no idea how your equipment works, but urge you to find out.

It's not polite to show other people your equipment.

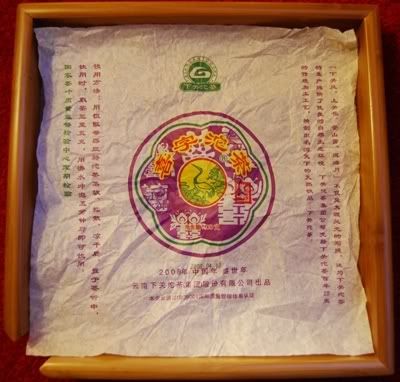

You swallow the tea. That acidity might have been swelling into a huigan [HWEE-GAN], which is lit. return-sweet. You swallow, and you get a resounding crescendo happening in the throat. This can dwell for yonks, in a good tea. Lingering, lingering, making the mouth water more and more, a decent huigan is sometimes worth the price of admission alone. Needless to say, I've found that "better" teas have longer, more powerful, more pronounced, more saliva-inducing huigan - but it can vary. Some huigan come and go quite quickly, some build to a crescendo, some remain constant and loud throughout. There are as many varieties as there are different leaves and methods of production.

At the same time as the huigan, you're getting some aroma heading upstairs from the throat into the nose. This "after-aroma" is sometimes called yunxiang [YOON SHEE-ANG] by some teafolk, lit. rhyme aroma. Here, the character for rhyme means... complementary charm, that harmonious charm often classically associated with women that have reached maturity, in some sense. Chinese is a suggestive language. If our language is technically Romantic, Chinese is actually romantic. What does the yunxiang remind you of? I get my kicks from those that leave plenty of tobacco back there - but equal pleasures abound in the floral equivalents, or buttery-sweetness of some others, or the pure leatheriness of a good Banzhang.

Some folk like to include chayun [CHA YOON] in their tasting vocabularies. This can mean varying things depending on whom you speak with, but the characters literally mean tea-rhyme, where "rhyme" is the complementary charm mentioned above. I take it to mean a gamut of sensations that are felt alongside the flavour, aroma, and huigan. Some teafolk include the texture of the soup in this term, some include the effervescence, some neither.

At the same time as the huigan, you're getting some aroma heading upstairs from the throat into the nose. This "after-aroma" is sometimes called yunxiang [YOON SHEE-ANG] by some teafolk, lit. rhyme aroma. Here, the character for rhyme means... complementary charm, that harmonious charm often classically associated with women that have reached maturity, in some sense. Chinese is a suggestive language. If our language is technically Romantic, Chinese is actually romantic. What does the yunxiang remind you of? I get my kicks from those that leave plenty of tobacco back there - but equal pleasures abound in the floral equivalents, or buttery-sweetness of some others, or the pure leatheriness of a good Banzhang.

Some folk like to include chayun [CHA YOON] in their tasting vocabularies. This can mean varying things depending on whom you speak with, but the characters literally mean tea-rhyme, where "rhyme" is the complementary charm mentioned above. I take it to mean a gamut of sensations that are felt alongside the flavour, aroma, and huigan. Some teafolk include the texture of the soup in this term, some include the effervescence, some neither.

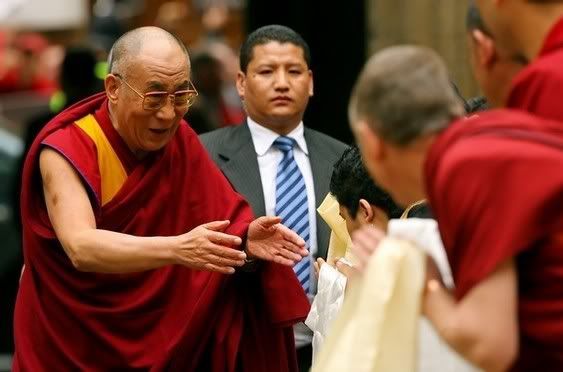

The tea will also affect your body in some way. Yes, I'm talking about our old friend, Mr. Qi.

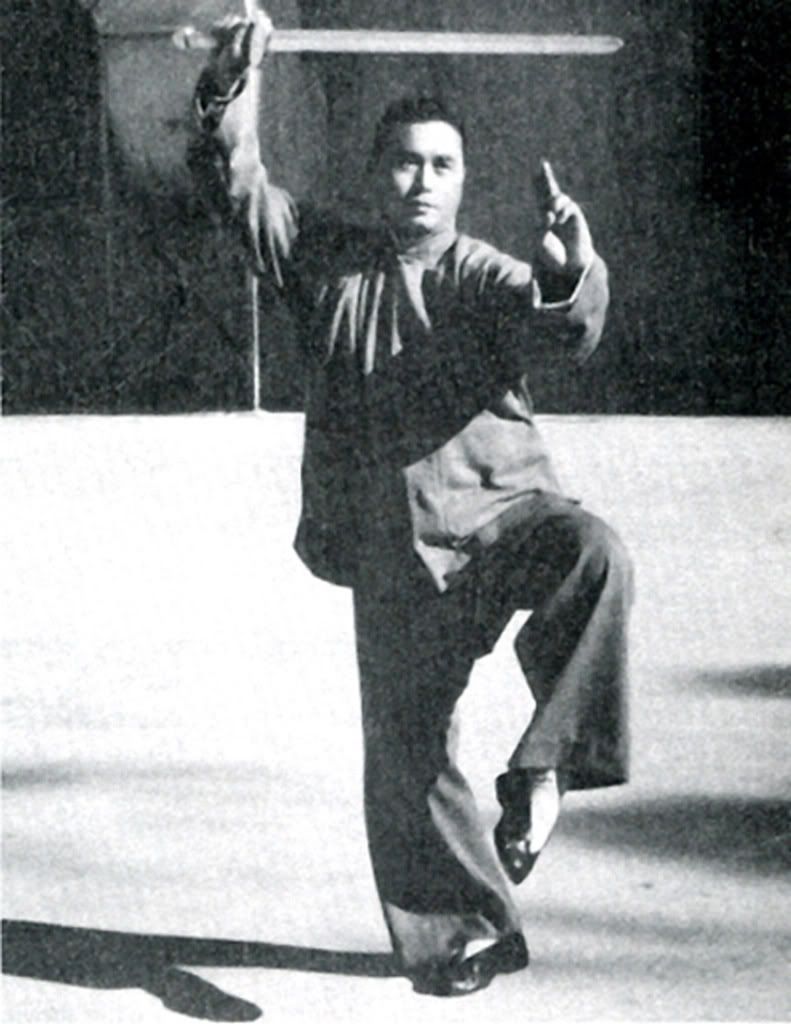

To some folk, chaqi is that mystical force that flows through us, surrounds and binds us; it's in you, me, the tree, the rock, everywhere. Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter. To others, chaqi is a blanket term for describing subtle physiological phenomena. Some folk relate it to the parasympathetic nervous system. Some folk use it to put out candles and throw people across a room (or pull x-wing fighters out of swamps in the Dagoba System). My own opinion is one of agnosticism on the subject of qi. Both Western and Eastern descriptions seem useful, and I wouldn't want to discount either as both are equally right, and equally wrong. I've done loads of qigong [chi'kung] in my time, am a (semi-) regular taijiquan [t'ai chi ch'uan] practitioner, but also a paid-up member of the Science Club (discounts available on scientific calculators and pocket-protectors). So, I take it all and use what works.

To some folk, chaqi is that mystical force that flows through us, surrounds and binds us; it's in you, me, the tree, the rock, everywhere. Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter. To others, chaqi is a blanket term for describing subtle physiological phenomena. Some folk relate it to the parasympathetic nervous system. Some folk use it to put out candles and throw people across a room (or pull x-wing fighters out of swamps in the Dagoba System). My own opinion is one of agnosticism on the subject of qi. Both Western and Eastern descriptions seem useful, and I wouldn't want to discount either as both are equally right, and equally wrong. I've done loads of qigong [chi'kung] in my time, am a (semi-) regular taijiquan [t'ai chi ch'uan] practitioner, but also a paid-up member of the Science Club (discounts available on scientific calculators and pocket-protectors). So, I take it all and use what works.

The Science Club does not have oak panelling or first editions of Principia Mathematica.

Whether you think chaqi is voodoo or life-affirming, your body reacts in some way to the act of ingesting tea. I believe, based on observing the responses of my own physiology to tea, that it is possible to separate the effects caused by caffeine and Other Stuff. Whether that remainder be theanines, complexes of organovibronucleotides, or the sheer rampant power of Grandmaster Qi, there is some non-caffeine effect induced by tea. Let's call that effect "chaqi" for the sake of shared discourse.

Sometimes, this chaqi can be calming. Soothing. Highly relaxing, in an almost narcotic sense. I remember sitting down at an afternoon conference session some time ago with a huge feeling of post-pu'er narcotic bliss. Like, far out, man. Sometimes, this chaqi can be brutal, shaking, vibrant, energising. Sometimes there is no chaqi whatsoever.

In old teas, much of the flavour can have devolved into something less exciting, but the chaqi can be as huge as a star destroyer. I have previously called these CDVs (Chaqi Delivery Vehicles) and take every opportunity to wheel out that old chestnut. It's a sad fact of an engineering education that TLAs* become a thing of humour. My travel tea kit is an MGP - Mobile Gongfucha Platform. Etc.

*Three-letter acronyms

My favourite photographs in tea magazines are the get-togethers of people wearing new age clothes, eyes closed, enjoying their chaqi. If there was any article that I would not want my friends to see, lest they truly discover how sad I really am, that would be it.*

*I like to think that I'm not actually this shallow. My friends are fully aware of the immensity of my sadness, and I theirs. And I have some really sad friends. Mind you, I'm the one quoting Master Yoda, so that speaks volumes.

Sometimes, this chaqi can be calming. Soothing. Highly relaxing, in an almost narcotic sense. I remember sitting down at an afternoon conference session some time ago with a huge feeling of post-pu'er narcotic bliss. Like, far out, man. Sometimes, this chaqi can be brutal, shaking, vibrant, energising. Sometimes there is no chaqi whatsoever.

In old teas, much of the flavour can have devolved into something less exciting, but the chaqi can be as huge as a star destroyer. I have previously called these CDVs (Chaqi Delivery Vehicles) and take every opportunity to wheel out that old chestnut. It's a sad fact of an engineering education that TLAs* become a thing of humour. My travel tea kit is an MGP - Mobile Gongfucha Platform. Etc.

*Three-letter acronyms

My favourite photographs in tea magazines are the get-togethers of people wearing new age clothes, eyes closed, enjoying their chaqi. If there was any article that I would not want my friends to see, lest they truly discover how sad I really am, that would be it.*

*I like to think that I'm not actually this shallow. My friends are fully aware of the immensity of my sadness, and I theirs. And I have some really sad friends. Mind you, I'm the one quoting Master Yoda, so that speaks volumes.

Say hello to our old friend, Mr. Qi.

There's plenty to check out when you're next looking critically at your tea, but I advise you to read this article with a sensible degree of skepticism. If you study anything too much, you'll kill it. Find what you enjoy, and hang onto it. And don't worry about people telling you that you suck. When it comes to your tastes, you are the only arbiter. Just because Grandmaster Big Jimmy has been writing about tea for years doesn't mean you have to copy him. Hang in there, and you'll be your own expert within a few hundred pots.*

*Exact number of pots required to become an expert may vary. Please send cheques for your "tea expert" certificates to me at the usual address. We offer certification to suit a range of budgets.

*Exact number of pots required to become an expert may vary. Please send cheques for your "tea expert" certificates to me at the usual address. We offer certification to suit a range of budgets.