I should drink more lucha. The real obstacle is drinking it before it dies, because I usually cannot get through large quantities of green tea within a year. One solution would be to resort to drinking it in my office, but that is rather an ignominious fate for good tea.

The only other Sichuan [ser-chooan] tea that I've had before is Zhuyeqing [bamboo-leaf green], which is a bulbous, tippy tea that hangs vertically in the water, rather like a seahorse. It's also one of my favourites greens, and not widely available outside China.

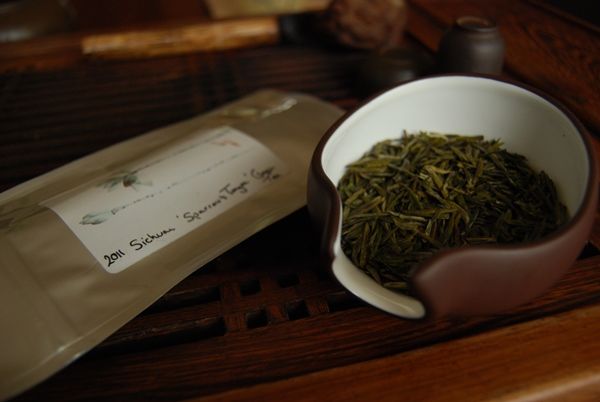

So, then, particularly thanks are due to Mr. and Mrs. Essence of Tea for kindly providing me with a sample of this most unusual tea: a queshe [choo'air sher, "sparrow tongue"] tea from the same province.

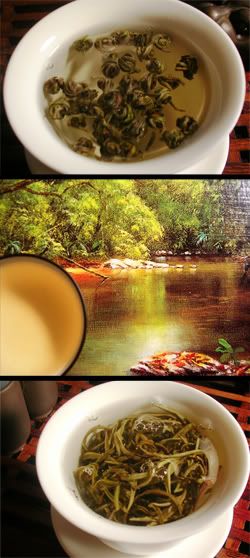

I'm used to "queshe" being used to describe a grade of Longjing, and so it is quite exciting to try an entirely new variety of tea - new to my limited tastes, that is. As shown above, it is a light yellow, which has a hint of brown about it. This suggests roasting to me, and, lo and behold, it has a lot in common with the roasted nature of Longjing.

Like good lucha, it is grassy, fresh, and this sample is quite full in the mouth, reminding me that these are good leaves. As with the Essence of Tea 2011 Xiping Tieguanyin, it is perhaps a little light for my tastes; I get the impression that Mr. and Mrs. Essence like their teas to be fine, delicate, and rarefied.

The "sparrow tongue" is shown above. Coincidentally, the same phrase is used to describe a common move in taijiquan, whereby one spreads one's arms in a forward motion, simultaneously warding off an attacking strike, and directing a counter-attacking push to the opponent's centre of gravity.

The price is £28/100g, which is along the same lines as wulong pricing. I almost never buy tea that isn't pu'ercha, and so such prices seem rather lofty by comparison. It seems that the market will bear significantly higher prices in wyulong and lucha, perhaps because their provenance is (generally, across most vendors) more opaque, which can be attributed to the lack of "branding", due to the nature of lucha and wulong. Perhaps pu'ercha benefits from such branding - a 2008 ABC cake from XYZ factory is traceable and has a history, whereas a "200X wulong from PQR region of KLM province" is less so. Certainly, pu'ercha customers benefit, at least.

Essence of Tea products try hard to relieve this opacity, and are generous in the information that they provide: this "queshe" was bought in Dashui village in northern Sichuan.

Thanks again to Nada for a thoroughly enjoyable session with a type of tea that I'd like to encounter more; Sichuan greens seem, from my N = 2 sample, to be really rather nice.