Teas brewed for me in Maliandao generally tasted about 50% as pleasant as the same teas turned out when brewed at home.

This particular tea, the 2007 Simao maocha, makes for a good comparison of waters, as I have tried it in several locations: Maliandao, a Beijing hotel, in my office, and at home - with water quality increasing from worst to best in that order (Maliandao worst, home best).

For the insular purposes of my notes, this tea was 120 RMB [~£9, $18] per banjin [250g], from the sweet girl who spoke no English, and whose boyfriend was cooking dinner.

Good, whole leaves with plenty of tips, which give a correspondingly grape-like, green lid. The wenxiangbei gives a tangy, mushroom-like aroma, which exactly follows into the mouth. There is plenty of exciting acidity in the finish, from which comes the huigan, while the texture is almost creamy. The soup is a solid yellow.

It's a chunky, mushroom-like tea which I like very much - one for drinking immediately, with plenty of leaf. The wet leaves are all tip-and-bud systems, with good strength that suggests the effects of overfarming may not be omnipresent. A fine grade.

Its effect with water is fascinating: this is a very decent tea, but I distinctly remember how it tasted in Maliandao: an echo of its future glory, but standing out enough from its Maliandao peers to encourage me to buy it. All other brewing parameters being almost identical to my own, it has to be the water that is the differing factor.

Using a similarly poor-quality water in my office almost exactly reproduced the pedestrian Maliandao character, while giving it the benefit of some decent water (Scottish Mountain) at home was like polishing a grubby diamond: the results were brilliant, fresh, and thoroughly enjoyable.

This seems to be a constant tale for my Maliandao teas: they taste delicious at home. An education in water, again.

Addendum

March, 2012

It has been five years since I bought and last tried this maocha - I have been aging this maocha in a tightly-sealed cardboard tube (pictured below), and a smaller amount in a rosewood box so that the majority in the tube need not be disturbed.

Don't worry - it's not really longjing

As it turns out, the rosewood container imparted some rosewood charateristics to the 50g or so of maocha that it contained. I consumed this in my lab, but wondered as to the majority of the leaves, aging steadily in their cardboard tube.

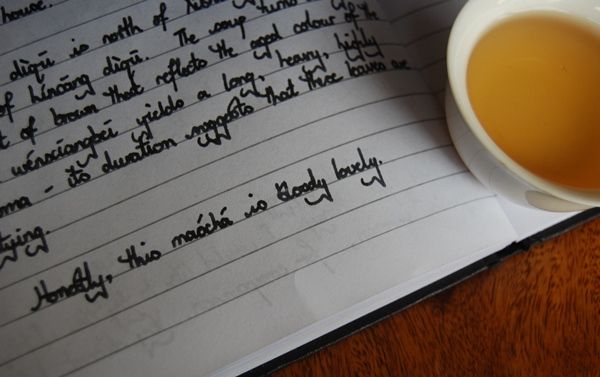

The immediate impression is of a maocha that has darkened considerably in the half-decade that it's been aging here in England. The green character that I remember from before has been entirely replaced by a healthy brown shade. I'm amazed that I seem to recall the taste-memory of this maocha, even though it has been five years since I encountered it last.

Simao prefecture is directly north of Xishuangbanna, and south of Lincang. Its produce seems, to my recollection, to be more akin to the latter than the former: rustic, "granary", sweet, potent. The aroma, uncaged after its years in isolation, brings this back to mind.

Even though the cardboard tube has been closed for five years, the tea has aged noticeably. I deliberately keep my maocha stoerd under more tightly-constrained conditions of airflow than my cakes, because I (rightly or wrongly) associate loose leaves as being at risk of losing their character. Many's the aged maocha that I've tried that seems a touch spent, whereas the density of matter in a cake seems to age more robustly.

As shown in the picture above, I rather enjoyed this maocha. Despite being almost sealed, the soup has darkened from the acrid green-yellow purity of youth to a heavy orange. In the aroma cup, it is long, sweet, and potent - a great sign.

Vibrant, mouthwatering, tantalising - the 2007 version of me really managed to buy a good tea in this instance. It is like a gift from the past, and a highly encouraging episode. Its kuwei [good bitterness] remains strong, but it has broadened and deepened in its character to become richer and more enjoyable than the leafy green flavour of youth. Fantastic stuff.

Back in the tube it goes.

Addendum

October, 2014

The scent of the leaves remains that of the rosewood box in which they are stored, but the wenxiangbei is filled with sweet-and-granary Simao aroma. The brown tint to the soup is a further clue to its origin. I enjoy its "soft" and smooth flavour; its age has taken away any rough edges that it may have had. Is that pesticide?

2 comments:

With superior H2O, we go from pedestrian to contending perambulator. john

The environment also has something to do with it, I think. Maliandao is hardly a great drinking environment.

Post a Comment