I've had some data concerning humidity and temperature lying around for some time, and have yet to write them up; a

recent article by His Grace, the Duke of N prompted me to do so - these latter are always a great pleasure to read.

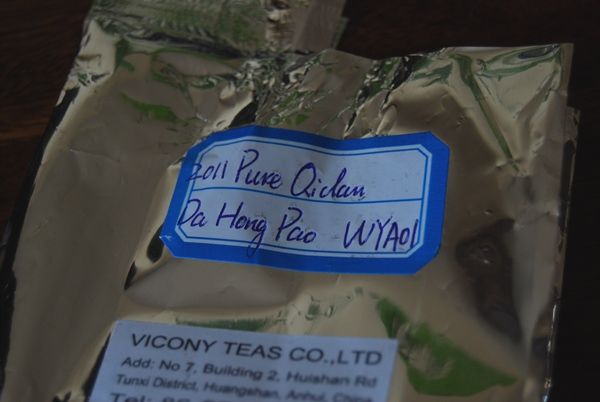

Some months ago, I accumulated weekly mean humidity and temperature data in a comparison of my local climate and that of Guangzhou, on the south end of the Chinese Mainland. I remember recently drinking some of Keng's delicious Singaporean-style shengpu, followed by a sample of something provided by my friend KC of Hong Kong, which caused me to wonder about the quantitative differences between the climates in my city, and in more traditional Oriental storage locations.

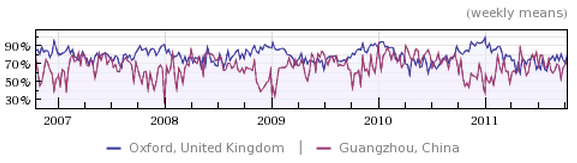

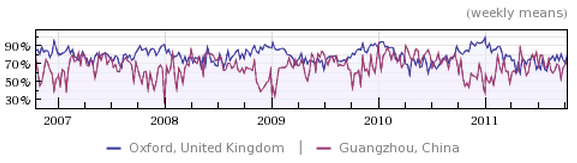

It probably should not have surprised me to learn that our damp little island has an amusingly high level of humidity. Lin Yutang, one of my favourite authors, attributes the "soft skin" of the English to this dampness. It is interesting to note in the above comparison, however, that our annual cycle appears to be in antiphase to that of Guangzhou: our humidity is at its highest in winter; the Chinese city's humidity peaks in summer (tropical). Of note is that the minimum Oxford humidity is around the maximum of the Guangzhou data.

The concern about humidity is that central heating can dry the air. I have attempted to mitigate this risk by not directly heating our tea-room; the air inside is instead maintained at the humidity of the exterior climate.

However, bringing tea back to England never really worried me in terms of humidity; my primary concern was due to the temperature.

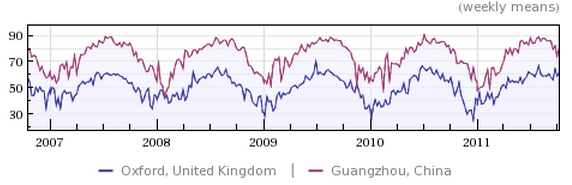

Oxford, and indeed England, is not famous for its high temperatures - we are a dark, northern-European kingdom, after all. The time-series above compares weekly mean temperatures for the same two cities, where we can see that there is a mean-shift of around 20 degrees Fahrenheit between the two. The mean temperature in Oxford is around 15 degrees Celcius, reaching some 20-to-25 degrees Celcius in the summer (although they have peaking at 34!), and descending to around 5 degrees Celcius in the winter.

The temperatures in my tea-room are maintained at a mean of around 20 degrees Celcius by the intrinsic heat of the structure of the house. This was, for a long term, my greatest concern, given that the humidity aspect was fine (and actually somewhat excessive).

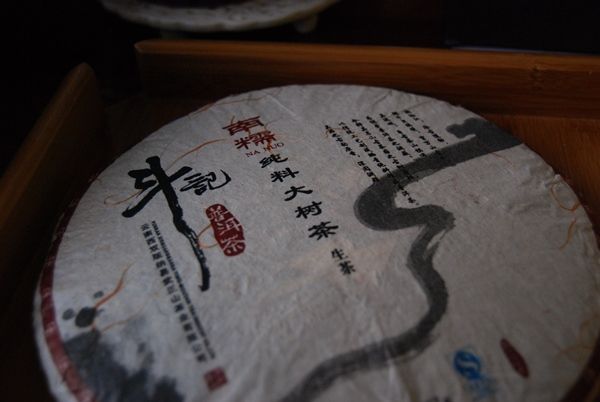

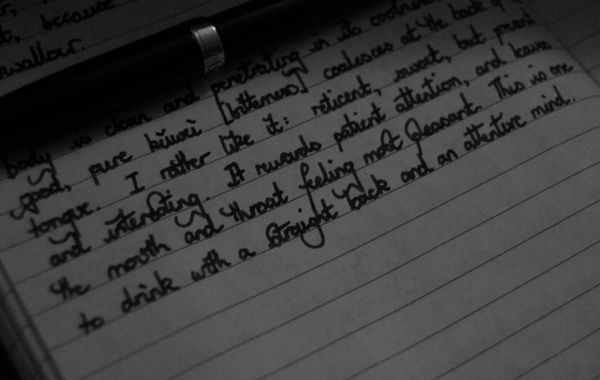

Ultimately, the true arbitors are the cakes themselves. Long-term readers of this humble blog may recall various re-tasting exercises (which are enumerated in my

Musings page, listed under "English Storage, I, II, ... V"). The evidence from our collection, and from that of teachums (inc. Nada) suggests that England's particular combination of excessive humidity and cooler temperatures results in some fairly decent aging. However, it is aging of a particularly curious sort.

At one end of the aging spectrum, we have "South China" (the geographical region, which I take to include Singapore, Taiwan, and Malaysia,), which results in the familiar form of "traditional storage", in which we taste classical aging profiles. Some of my favourite cakes are in this genre.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have Kunming- and Beijing-style storage, where humidity and temperatures are lower, and which result in the "dry" cakes that are becoming more prevalent.

Our English storage is a peculiar midpoint in this spectrum, due to the excess humidity, but low temperatures. The cakes are not aging rapidly and darkly, as do South-Chinese cakes, and yet they are aging rather well.

I cannot say how this environment, and the conclusions that we tentatively draw from the evidence acquired to date, can be extrapolated to other places. I wouldn't like to make any claims about storage elsewhere in Europe, or in the US, for example.

However, I will offer the now quite reasonable body of evidence that the combination of humidity and temperature, as shown in the graphs above, and which represents the conditions of storage in England, has resulted in some very pleasant outcomes in the last seven years.

His Grace, the Duke of N wrote that "temperature is the most important aspect", and it is here that I would like to offer a countervailing opinion.

While temperature is clearly important, the high humidity in England appears to be the deciding factor that keeps our cakes alive. Although we have lower temperatures here, the cakes are a fascinating combination of "traditional" and "dry" - they are slow to age, and yet they are moist, succulent, and flavoursome. In a recent round of re-tastes (notes of which are dispersed throughout my various articles), I have found many pleasures in our older cakes, aged here in England.

I speculate that the lower temperatures may merely reduce the duration of the "aging season" each year, which occurs during the summer. It could therefore be that our English cakes spend longer "asleep" each year than their Oriental counterparts, because our colder season (during which the cakes slumber) is longer.

However, our evidence suggests that Lin Yutang's tongue-in-cheek statement concerning the beneficial effect of the humidity on English skin may also extend to the preservation and development of flavour in our pu'ercha. It is a development much slower than that of cakes in South China, undoubtedly, but it is a long way from the "dry" profiles of Kunming and Beijing storage.

We'll see in another decade, I suppose, but the interim evidence is encouraging.

I consider our own experiences to be just one data-point in a much larger picture, as pu'ercha becomes distributed throughout the world.