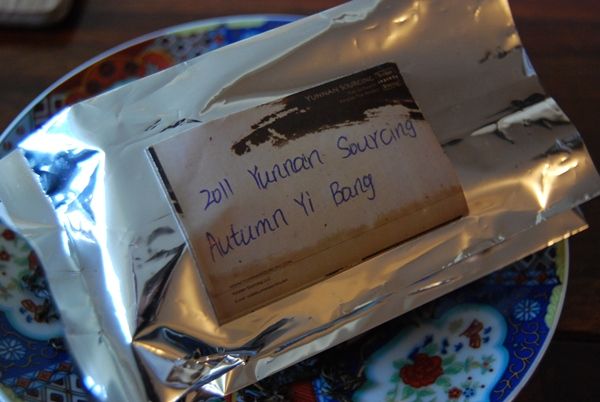

This is the second of two samples kindly provided by Vicony Teas, an outfit that operates from Anhui Province.

This shuixian-varietal yancha comes from Foguoyan [Buddha County], the same Wuyishan area from which the company's Qidan Dahongpao derives, which I enjoyed so much.

Older wulong requires refiring from time to time, to keep the moisture out. It is this relatively high level of maintenance that prevents me from keeping older examples in any quantity. Given my ability with such things, I'd be certain to ruin my tea, and find out about the mistake only after it was too late. Hence, I stick to aging pu'ercha: leaving something on a shelf is something that even I can manage.

The web-site of Vicony Teas notes that this was refired in September 2011, which suggests that it will last some time in my possession, at least. This is good - wulong lasts a long time on our shelves...

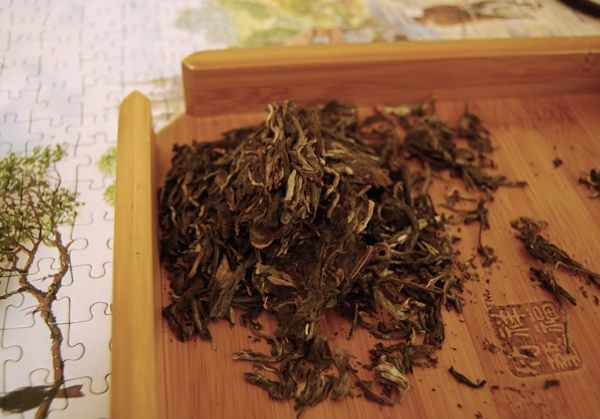

This particular shuixian [approximately shway shee'an] has been 60% oxidised, which comes across in the image above. The long, dark leaves have a gentle aroma of musky, sticky caramel.

As I've mentioned before, I pile a large quantity of leaves into the pot when brewing yancha. It's hard to overbrew, and tons of leaf therefore allows a richness of character. Even then, with a full pot, this tea was a touch on the quiet side, requiring long infusions right from the start in order to get some real character into the soup. Brewed for anything less than a significant period, it tastes a little empty, and is dominated by its roasting. This is always a danger for old wulong: it can sometimes taste of nothing more than its coating of roast, with the flavour of the leaf withering beneath.

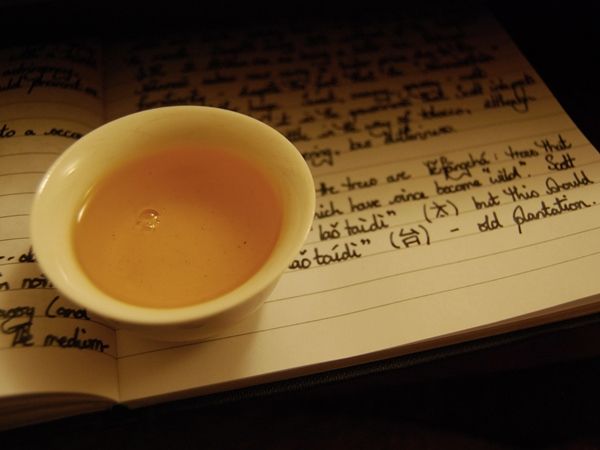

Keeping the infusion time up, however, yields a pleasant cup of warming, clean sweetness that continues in the sticky caramel manner of its aroma. With longer infusion times, the venerable old leaves give up a reminiscence of their old, original butteriness. Like the Qidan Dahongpao from the same company, it has a noticeable numbing effect (in a pleasant way) on the tip of the tongue, which, likening it to my experience of pu'ercha leaves, I assume to be indicative of good provenance and corresponding content in the leaves.

It doesn't take long for this tea to "revert to form", however, and become dominated by its roasted characteristics. While I had an enjoyable session, I suspect that this isn't a yancha that I would pursue in any great volume, and is a cautionary tale for those of us interested in older wulong. Thanks again to Richard for the opportunity to explore this mature tea.